BENLYSTA Powder for concentrate for solution for infusion Ref.[8926] Active ingredients: Belimumab

Source: European Medicines Agency (EU) Revision Year: 2024 Publisher: GlaxoSmithKline (Ireland) Limited, 12 Riverwalk, Citywest Business Campus, Dublin 24, Ireland

Pharmacodynamic properties

Pharmacotherapeutic group: Selective immunosuppressants

ATC code: L04AA26

Mechanism of action

Belimumab is a human IgG1λ monoclonal antibody specific for soluble human B Lymphocyte Stimulator protein (BLyS, also referred to as BAFF and TNFSF13B). Belimumab blocks the binding of soluble BLyS, a B cell survival factor, to its receptors on B cells. Belimumab does not bind B cells directly, but by binding BLyS, belimumab inhibits the survival of B cells, including autoreactive B cells, and reduces the differentiation of B cells into immunoglobulin-producing plasma cells.

BLyS levels are elevated in patients with SLE and other autoimmune diseases. There is an association between plasma BLyS levels and SLE disease activity. The relative contribution of BLyS levels to the pathophysiology of SLE is not fully understood.

Pharmacodynamic effects

Changes in biomarkers were seen in clinical trials with Benlysta administered intravenously. In adult patients with SLE with hypergammaglobulinemia, normalization of IgG levels was observed by Week 52 in 49% and 20% of patients receiving Benlysta and placebo, respectively.

In patients with SLE with anti-dsDNA antibodies, 16% of patients treated with Benlysta converted to antidsDNA negative compared with 7% of the patients receiving placebo by Week 52.

In patients with SLE with low complement levels, normalization of C3 and C4 was observed by Week 52 in 38% and 44% of patients receiving Benlysta and in 17% and 18% of patients receiving placebo, respectively.

Of the anti-phospholipid antibodies, only anti-cardiolipin antibody was measured. For anti-cardiolipin IgA antibody a 37% reduction at Week 52 was seen (p=0.0003), for anti-cardiolipin IgG antibody a 26% reduction at Week 52 was seen (p=0.0324) and for anti-cardiolipin IgM a 25% reduction was seen (p = NS, 0.46).

Changes in B cells (including naïve, memory and activated B cells, and plasma cells) and IgG levels occurring in patients with SLE during ongoing treatment with intravenous belimumab were followed in a long-term uncontrolled extension study. After 7 and a half years of treatment (including the 72-week parent study), a substantial and sustained decrease in various B cell subsets was observed leading to 87% median reduction in naïve B cells, 67% in memory B cells, 99% in activated B cells, and 92% median reduction in plasma cells after more than 7 years of treatment. After about 7 years, a 28% median reduction in IgG levels was observed, with 1.6% of subjects experiencing a decrease in IgG levels to below 400 mg/dL. Over the course of the study, the reported incidence of AEs generally remained stable or declined.

In patients with active lupus nephritis, following treatment with Benlysta (10 mg/kg intravenously) or placebo, there was an increase in serum IgG levels which was associated with decreased proteinuria. Relative to placebo, smaller increases in serum IgG levels were observed in the Benlysta group as expected with the known mechanism of belimumab. At Week 104, the median percent increase from baseline in IgG was 17% for Benlysta and 37% for placebo. Reductions in autoantibodies, increases in complement, and reductions in circulating total B cells and B-cell subsets observed were consistent with the SLE studies.

In one study in paediatric patients with SLE (6 to 17 years of age) the pharmacodynamic response was consistent with the adult data.

Immunogenicity

Assay sensitivity for neutralising antibodies and non-specific anti-drug antibody (ADA) is limited by the presence of active drug in the collected samples. The true occurrence of neutralising antibodies and non-specific anti-drug antibody in the study population is therefore not known. In the two Phase III SLE studies in adults, 4 of the 563 (0.7%) patients in the 10 mg/kg group and 27 out of 559 (4.8%) patients in the 1 mg/kg group tested positive for persistent presence of anti-belimumab antibodies. Among persistent-positive subjects in the Phase III SLE studies, 1/10 (10%), 2/27 (7%) and ¼ (25%) subjects in the placebo, 1 mg/kg and 10 mg/kg groups, respectively, experienced infusion reactions on a dosing day; these infusion reactions were all non-serious and mild to moderate in severity. Few patients with ADA reported serious/severe AEs. The rates of infusion reactions among persistent-positive subjects were comparable to the rates for ADA negative patients of 75/552 (14%), 78/523 (15%), and 83/559 (15%) in the placebo, 1 mg/kg and 10 mg/kg groups, respectively.

In the lupus nephritis study where 224 patients received Benlysta 10 mg/kg intravenously, no anti-belimumab antibodies were detected.

In one study in 6 to 17-year-old paediatric patients with SLE (n=53), none of the patients developed anti-belimumab antibodies.

Clinical efficacy and safety

SLE

Intravenous infusion in adults

The efficacy of Benlysta administered intravenously was evaluated in 2 randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled studies in 1684 patients with a clinical diagnosis of SLE according to the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) classification criteria. Patients had active SLE disease, defined as a SELENA-SLEDAI (SELENA = Safety of Estrogens in Systemic Lupus Erythematosus National Assessment; SLEDAI = Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Disease Activity Index) score ≥6 and positive anti-nuclear antibody (ANA) test results (ANA titre ≥1:80 and/or a positive anti-dsDNA [≥30 units/mL]) at screening. Patients were on a stable SLE treatment regimen consisting of (alone or in combination): corticosteroids, anti-malarials, NSAIDs or other immunosuppressives. The two studies were similar in design except that BLISS-76 was a 76-week study and BLISS-52 was a 52-week study. In both studies the primary efficacy endpoint was evaluated at 52 weeks.

Patients who had severe active lupus nephritis and patients who had severe active central nervous system (CNS) lupus were excluded.

BLISS-76 was conducted primarily in North America and Western Europe. Background medicinal products included corticosteroids (76%; >7.5 mg/day 46%), immunosuppressives (56%), and anti-malarials (63%).

BLISS-52 was conducted in South America, Eastern Europe, Asia, and Australia. Background medicinal products included corticosteroids (96%; >7.5 mg/day 69%), immunosuppressives (42%), and antimalarials (67%).

At baseline 52% of patients had high disease activity (SELENA SLEDAI score ≥10), 59% of patients had mucocutaneous, 60% had musculoskeletal, 16% had haematological, 11% had renal and 9% had vascular organ domain involvement (BILAG A or B at baseline).

The primary efficacy endpoint was a composite endpoint (SLE Responder Index) that defined response as meeting each of the following criteria at Week 52 compared with baseline:

- ≥4-point reduction in the SELENA-SLEDAI score, and

- no new British Isles Lupus Assessment Group (BILAG) A organ domain score or 2 new BILAG B organ domain scores, and

- no worsening (<0.30 point increase) in Physician’s Global Assessment score (PGA)

The SLE Responder Index measures improvement in SLE disease activity, without worsening in any organ system, or in the patient’s overall condition.

Table 1. Response rate at Week 52:

| Response | BLISS-76 | BLISS-52 | BLISS-76 and BLISS-52 pooled | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Placebo1 (n=275) | Benlysta 10 mg/kg1 (n=273) | Placebo1 (n=287) | Benlysta 10 mg/kg1 (n=290) | Placebo1 (n=562) | Benlysta 10 mg/kg1 (n=563) | |

| SLE responder index Observed difference vs. placebo Odds ratio (95% CI) vs. placebo | 33.8% | 43.2% (p=0.021) 9.4% 1.52 (1.07, 2.15) | 43.6% | 57.6% (p=0.0006) 14.0% 1.83 (1.30, 2.59) | 38.8% | 50.6% (p<0.0001) 11.8% 1.68 (1.32, 2.15) |

| Components of SLE responder index | ||||||

| Percent of patients with reduction in SELENA- SLEDAI ≥4 | 35.6% | 46.9% (p=0.006) | 46.0% | 58.3% (p=0.0024) | 40.9% | 52.8% (p<0.0001) |

| Percent of patients with no worsening by BILAG index | 65.1% | 69.2% (p=0.32) | 73.2% | 81.4% (p=0.018) | 69.2% | 75.5% (p=0.019) |

| Percent of patients with no worsening by PGA | 62.9% | 69.2% (p=0.13) | 69.3% | 79.7% (p=0.0048) | 66.2% | 74.6% (p=0.0017) |

1 All patients received standard therapy

In a pooled analysis of the two studies, the percentage of patients receiving >7.5 mg/day prednisone (or equivalent) at baseline, whose average corticosteroid dose was reduced by at least 25% to a dose equivalent to prednisone ≤7.5 mg/day during Weeks 40 through 52, was 17.9% in the group receiving Benlysta and 12.3% in the group receiving placebo (p=0.0451).

Flares in SLE were defined by the modified SELENA SLEDAI SLE Flare Index. The median time to the first flare was delayed in the pooled group receiving Benlysta compared to the group receiving placebo (110 vs. 84 days, hazard ratio = 0.84, p=0.012). Severe flares were observed in 15.6% of the Benlysta group compared to 23.7% of the placebo group over the 52 weeks of observation (observed treatment difference = -8.1%; hazard ratio = 0.64, p=0.0011).

Benlysta demonstrated improvement in fatigue compared with placebo measured by the FACIT-Fatigue scale in the pooled analysis. The mean change of score at Week 52 from baseline is significantly greater with Benlysta compared to placebo (4.70 vs. 2.46, p=0.0006).

Univariate and multivariate analysis of the primary endpoint in pre-specified subgroups demonstrated that the greatest benefit was observed in patients with higher disease activity including patients with SELENA SLEDAI scores ≥10, or patients requiring steroids to control their disease, or patients with low complement levels.

Post-hoc analysis has identified high responding subgroups such as those patients with low complement and positive anti-dsDNA at baseline, see Table 2 for results of this example of a higher disease activity group.

Of these patients, 64.5% had SELENA SLEDAI scores ≥10 at baseline.

Table 2. Patients with low complement and positive anti-dsDNA at baseline:

| Subgroup | Anti-dsDNA positive AND low complement | |

|---|---|---|

| BLISS-76 and BLISS-52 pooled data | Placebo (n=287) | Benlysta 10 mg/kg (n=305) |

| SRI response rate at Week 52 (%) Observed treatment difference vs. placebo (%) | 31.7 | 51.5 (p<0.0001) 19.8 |

| SRI response rate (excluding complement and anti- dsDNA changes) at Week 52 (%) Observed treatment difference vs. placebo (%) | 28.9 | 46.2 (p<0.0001) 17.3 |

| Severe flares over 52 weeks Patients experiencing a severe flare (%) Observed treatment difference vs. placebo (%) Time to severe flare [Hazard ratio (95% CI)] | 29.6 | 19.0 10.6 0.61 (0.44, 0.85) (p=0.0038) |

| Prednisone reduction by ≥25% from baseline to ≤7.5 mg/day during weeks 40 through 521 (%) Observed treatment difference vs. placebo (%) | (n=173) 12.1 | (n=195) 18.5 (p=0.0964) 6.3 |

| FACIT-fatigue score improvement from baseline at Week 52 (mean) Observed treatment difference vs. placebo (mean difference) | 1.99 | 4.21 (p=0.0048) 2.21 |

| BLISS-76 study only | Placebo (n=131) | Benlysta 10 mg/kg (n=134) |

| SRI response rate at Week 76 (%) Observed treatment difference vs. placebo (%) | 27.5 | 39.6 (p=0.0160) 12.1 |

1 Among patients with baseline prednisone dose >7.5 mg/day.

The efficacy and safety of Benlysta in combination with a single cycle of rituximab have been studied in a Phase III, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled 104-week study including 292 patients (BLISS-BELIEVE). The primary endpoint was the proportion of subjects with a state of disease control defined as a SLEDAI-2K score ≤2, achieved without immunosuppressants and with corticosteroids at a prednisone equivalent dose of ≤5 mg/day at Week 52. This was achieved in 19.4% (n=28/144) of the patients treated with Benlysta in combination with rituximab and in 16.7% (n=12/72) of the patients treated with Benlysta in combination with placebo (odds ratio 1.27; 95% CI: 0.60, 2.71; p=0.5342). A higher frequency of adverse events (91.7% vs. 87.5%), serious adverse events (22.2% vs. 13.9%) and serious infections (9.0% vs. 2.8%) were observed in patients treated with Benlysta in combination with rituximab as compared to Benlysta in combination with placebo.

Lupus nephritis

In the intravenous SLE studies, described above, patients who had severe active lupus nephritis were excluded; however, 11% of patients had renal organ domain involvement at baseline (based on BILAG A or B assessment). The following study in active lupus nephritis has been conducted.

The efficacy and safety of Benlysta 10 mg/kg administered intravenously over a 1-hour period on Days 0, 14, 28, and then every 28 days, were evaluated in a 104-week randomised (1:1), double-blind, placebo-controlled, Phase III study (BEL114054) in 448 patients with active lupus nephritis. The patients had a clinical diagnosis of SLE according to ACR classification criteria, biopsy proven lupus nephritis Class III, IV, and/or V and had active renal disease at screening requiring standard therapy. Standard therapy included corticosteroids, 0 to 3 intravenous administrations of methylprednisolone (500 to1000 mg per administration), followed by oral prednisone 0.5 to 1 mg/kg/day with a total daily dose ≤60 mg/day and tapered to ≤10 mg/day by Week 24, with:

- mycophenolate mofetil 1 to 3 g/day orally or mycophenolate sodium 720 to 2160 mg/day orally for induction and maintenance, or

- cyclophosphamide 500 mg intravenously every 2 weeks for 6 infusions for induction followed by azathioprine orally at a target dose of 2 mg/kg/day for maintenance.

This study was conducted in Asia, North America, South America, and Europe. Patient median age was 31 years (range: 18 to 77 years); the majority (88%) were female.

The primary efficacy endpoint was Primary Efficacy Renal Response (PERR) at Week 104 defined as a response at Week 100 confirmed by a repeat measurement at Week 104 of the following parameters: urinary protein:creatinine ratio (uPCR) ≤700 mg/g (79.5 mg/mmol) and estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) ≥60 mL/min/1.73 m² or no decrease in eGFR of >20% from pre-flare value.

The major secondary endpoints included:

- Complete Renal Response (CRR) defined as a response at Week 100 confirmed by a repeat measurement at Week 104 of the following parameters: uPCR <500 mg/g (56.8 mg/mmol) and eGFR ≥90 mL/min/1.73 m² or no decrease in eGFR of >10% from pre-flare value.

- PERR at Week 52.

- Time to renal-related event or death (renal-related event defined as first event of end-stage renal disease, doubling of serum creatinine, renal worsening [defined as increased proteinuria, and/or impaired renal function], or receipt of renal disease-related prohibited therapy).

For PERR and CRR endpoints, steroid treatment had to be reduced to ≤10 mg/day from Week 24 to be considered a responder. For these endpoints, patients who discontinued treatment early, received prohibited medication, or withdrew from the study early were considered non-responders.

The proportion of patients achieving PERR at Week 104 was significantly higher in patients receiving Benlysta compared with placebo. The major secondary endpoints also showed significant improvement with Benlysta compared with placebo (Table 3).

Table 3. Efficacy results in adult patients with lupus nephritis:

| Efficacy endpoint | Placebo (n=223) | Benlysta 10 mg/kg (n=223) | Observed difference vs. placebo | Odds/Hazard ratio vs. placebo (95% CI) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PERR at Week 1041 Responders | 32.3% | 43.0% | 10.8% | OR 1.55 (1.04, 2.32) | 0.0311 |

| Components of PERR | |||||

| Urine protein:creatinine ratio ≤700 mg/g (79.5 mg/mmol) | 33.6% | 44.4% | 10.8% | OR 1.54 (1.04, 2.29) | 0.0320 |

| eGFR ≥60 mL/min/1.73 m² or no decrease in eGFR from pre-flare value of >20% | 50.2% | 57.4% | 7.2% | OR 1.32 (0.90, 1.94) | 0.1599 |

| Not treatment failure3 | 74.4% | 83.0% | 8.5% | OR 1.65 (1.03, 2.63) | 0.0364 |

| CRR at Week 1041 Responders | 19.7% | 30.0% | 10.3% | OR 1.74 (1.11, 2.74) | 0.0167 |

| Components of CRR | |||||

| Urine protein:creatinine ratio <500 mg/g (56.8 mg/mmol) | 28.7% | 39.5% | 10.8% | OR 1.58 (1.05, 2.38) | 0.0268 |

| eGFR ≥90 mL/min/1.73 m² or no decrease in eGFR from pre-flare value of >10% | 39.9% | 46.6% | 6.7% | OR 1.33 (0.90, 1.96) | 0.1539 |

| Not treatment failure3 | 74.4% | 83.0% | 8.5% | OR 1.65 (1.03, 2.63) | 0.0364 |

| PERR at Week 521 Responders | 35.4% | 46.6% | 11.2% | OR 1.59 (1.06, 2.38) | 0.0245 |

| Time to renal-related event or death1 Percentage of patients with event2 Time to event [Hazard ratio (95% CI)] | 28.3% | 15.7% | - - | HR 0.51 (0.34, 0.77) | 0.0014 |

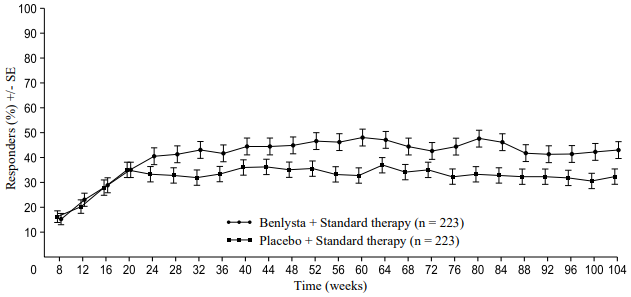

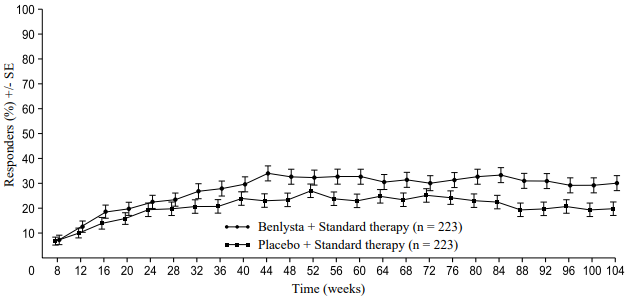

A numerically greater percentage of patients receiving Benlysta achieved PERR beginning at Week 24 compared with placebo, and this treatment difference was maintained through to Week 104. Beginning at Week 12, a numerically greater percentage of patients receiving Benlysta achieved CRR compared with placebo and the numerical difference was maintained through to Week 104 (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Response rates in adults with lupus nephritis by visit:

Primary Efficacy Renal Response (PERR)

Complete Renal Response (CRR)

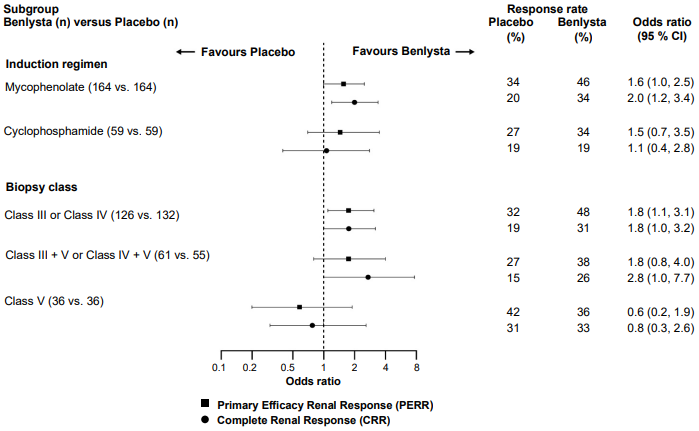

In descriptive subgroup analyses, key efficacy endpoints (PERR and CRR) were examined by induction regimen (mycophenolate or cyclophosphamide) and biopsy class (Class III or IV, Class III + V or Class IV + V, or Class V) (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Odds ratio of PERR and CRR at Week 104 across subgroups:

Age and race

Age

There were no observed differences in efficacy or safety in SLE patients ≥ 65 years who received Benlysta intravenously or subcutaneously compared to the overall population in placebo-controlled studies; however, the number of patients aged ≥65 years (62 patients for efficacy and 219 for safety) is not sufficient to determine whether they respond differently to younger patients.

Black patients

Benlysta was administered intravenously to black patients with SLE in a randomised (2:1), double-blind, placebo-controlled, 52-week Phase III/IV study (EMBRACE). Efficacy was evaluated in 448 patients. The proportion of black patients achieving an SRI-S2K response was higher in patients receiving Benlysta but the difference was not statistically significant compared with placebo. However, consistent with results from other studies, in black patients with high disease activity (low complement and positive anti-dsDNA at baseline, n=141) the SRI-S2K response was 45.1% for Benlysta 10 mg/kg compared with 24.0% for placebo (odds ratio 3.00; 95% CI: 1.35, 6.68).

Paediatric population

The safety and efficacy of Benlysta was evaluated in a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, 52-week study (PLUTO) in 93 paediatric patients with a clinical diagnosis of SLE according to the ACR classification criteria. Patients had active SLE disease, defined as a SELENA-SLEDAI score ≥ 6 and positive autoantibodies at screening as described in the adult trials. Patients were on a stable SLE treatment regimen (standard of care) and had similar inclusion criteria as the adult studies. Patients who had severe active lupus nephritis, severe active CNS lupus, primary immunodeficiency, IgA deficiency or acute or chronic infections requiring management were excluded from the study. The study was conducted in the US, South America, Europe, and Asia. Patient median age was 15 years (range 6 to 17 years). In the 5- to 11-year-old-group (n=13) the SELENA-SLEDAI score ranged from 4 to 13, and in 12- to 17-year-old-group (n=79) the SELENA-SLEDAI score ranged from 4 to 20. The majority (94.6%) of patients were female. The study was not powered for any statistical comparisons and all data are descriptive.

The primary efficacy endpoint was the SLE Responder Index (SRI) at Week 52 as described in the adult intravenous trials. There was a higher proportion of paediatric patients achieving an SRI response in patients receiving Benlysta compared with placebo. The response for the individual components of the endpoint were consistent with that of the SRI (Table 4).

Table 4. Paediatric response rate at Week 52:

| Response1 | Placebo (n=40) | Benlysta 10 mg/kg (n=53) |

|---|---|---|

| SLE Responder Index (%) Odds ratio (95% CI) vs. placebo | 43.6 (17/39) | 52.8 (28/53) 1.49 (0.64, 3.46) |

| Components of SLE Responder Index | ||

| Percent of patients with reduction in SELENA-SLEDAI ≥4 (%) Odds ratio (95% CI) vs. placebo | 43.6 (17/39) | 54.7 (29/53) 1.62 (0.69, 3.78) |

| Percent of patients with no worsening by BILAG index (%) Odds ratio (95% CI) vs. placebo | 61.5 (24/39) | 73.6 (39/53) 1.96 (0.77, 4.97) |

| Percent of patients with no worsening by PGA (%) Odds ratio (95% CI) vs. placebo | 66.7 (26/39) | 75.5 (40/53) 1.70 (0.66, 4.39) |

1 Analyses excluded any subject missing a baseline assessment for any of the components (1 for placebo).

Among patients experiencing a severe flare, the median study day of the first severe flare was Day 150 in the Benlysta group and Day 113 in the placebo group. Severe flares were observed in 17.0% of the Benlysta group compared to 35.0% of the placebo group over the 52 weeks of observation (observed treatment difference = 18.0%; hazard ratio = 0.36, 95% CI: 0.15, 0.86). This was consistent with the findings from the adult intravenous clinical trials.

Using the Paediatric Rheumatology International Trials Organisation/American College of Rheumatology (PRINTO/ACR) Juvenile SLE Response Evaluation Criteria, a higher proportion of paediatric patients receiving Benlysta demonstrated improvement compared with placebo (Table 5).

Table 5. PRINTO/ACR response rate at Week 52:

| Proportion of patients with at least 50% improvement in any 2 of 5 components1 and no more than one of the remaining worsening by more than 30% | Proportion of patients with at least 30% improvement in 3 of 5 components1 and no more than one of the remaining worsening more than 30% | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Placebo n=40 | Benlysta 10 mg/kg n=53 | Placebo n=40 | Benlysta 10 mg/kg n=53 | |

| Response, n (%) | 14/40 (35.0) | 32/53 (60.4) | 11/40 (27.5) | 28/53 (52.8) |

| Observed difference vs. Placebo | 25.38 | 25.33 | ||

| Odds ratio (95% CI) vs. Placebo | 2.74 (1.15, 6.54) | 2.92 (1.19, 7.17) | ||

1 The five PRINTO/ACR components were percent change at Week 52 in: Parent’s Global Assessment (Parent GA), PGA, SELENA SLEDAI score, 24-hour proteinuria, and, Paediatric Quality of Life Inventory – Generic Core Scale (PedsQL GC) physical functioning domain score.

Pharmacokinetic properties

The intravenous pharmacokinetic parameters quoted below are based on population parameter estimates for the 563 patients with SLE who received Benlysta 10 mg/kg in the two Phase III studies.

Absorption

Benlysta is administered by intravenous infusion. Maximum serum concentrations of belimumab were generally observed at, or shortly after, the end of the infusion. The maximum serum concentration was 313 µg/mL (range: 173-573 µg/mL) based on simulating the concentration time profile using the typical parameter values of the population pharmacokinetic model.

Distribution

Belimumab was distributed to tissues with steady-state volume (Vss) of distribution of approximately 5 litres.

Biotransformation

Belimumab is a protein for which the expected metabolic pathway is degradation to small peptides and individual amino acids by widely distributed proteolytic enzymes. Classical biotransformation studies have not been conducted.

Elimination

Serum belimumab concentrations declined in a bi-exponential manner, with a distribution half-life of 1.75 days and terminal half-life 19.4 days. The systemic clearance was 215 mL/day (range: 69-622 mL/day).

Lupus nephritis study

A population pharmacokinetic analysis was conducted in 224 adult patients with lupus nephritis who received Benlysta 10 mg/kg intravenously (Days 0, 14, 28, and then every 28 days up to 104 weeks). In patients with lupus nephritis, due to renal disease activity, belimumab clearance was initially higher than observed in SLE studies; however, after 24 weeks of treatment and throughout the remainder of the study, belimumab clearance and exposure were similar to that observed in adult patients with SLE who received Benlysta 10 mg/kg intravenously.

Special patient populations

Paediatric population

The pharmacokinetic parameters are based on individual parameter estimates from a population pharmacokinetic analysis of 53 patients from a study in paediatric patients with SLE. Following intravenous administration of 10 mg/kg on Days 0, 14 and 28, and at 4-week intervals thereafter, belimumab exposures were similar between paediatric and adult SLE subjects. Steady-state geometric mean Cmax, Cmin, and AUC values were 305 µg/mL, 42 µg/mL, and 2569 day•µg/mL in the 5- to 11-year-old-group, and 317 µg/mL, 52 µg/mL, and 3126 day•µg/mL in the 12- to 17-year-old-group (n = 43).

Elderly

Benlysta has been studied in a limited number of elderly patients. Within the overall SLE intravenous study population, age did not affect belimumab exposure in the population pharmacokinetic analysis. However, given the small number of subjects ≥ 65 years, an effect of age cannot be ruled out conclusively.

Renal impairment

No specific studies have been conducted to examine the effects of renal impairment on the pharmacokinetics of belimumab. During clinical development Benlysta was studied in patients with SLE and renal impairment (261 subjects with moderate renal impairment, creatinine clearance ≥30 and <60 mL/min; 14 subjects with severe renal impairment, creatinine clearance ≥15 and <30 mL/min). The reduction in systemic clearance estimated by population PK modelling for patients at the midpoints of the renal impairment categories relative to patients with median creatinine clearance in the PK population (79.9 mL/min) were 1.4 % for mild (75 mL/min), 11.7 % for moderate (45 mL/min) and 24.0 % for severe (22.5 mL/min) renal impairment. Although proteinuria (≥ 2 g/day) increased belimumab clearance and decreases in creatinine clearance decreased belimumab clearance, these effects were within the expected range of variability. Therefore, no dose adjustment is recommended for patients with renal impairment.

Hepatic impairment

No specific studies have been conducted to examine the effects of hepatic impairment on the pharmacokinetics of belimumab. IgG1 molecules such as belimumab are catabolised by widely distributed proteolytic enzymes, which are not restricted to hepatic tissue and changes in hepatic function are unlikely to have any effect on the elimination of belimumab.

Body weight/Body Mass Index (BMI)

Weight-normalised belimumab dosing leads to decreased exposure for underweight subjects (BMI <18.5) and to increased exposure for obese subjects (BMI ≥30). BMI-dependent changes in exposure did not lead to corresponding changes in efficacy. Increased exposure for obese subjects receiving 10 mg/kg belimumab did not lead to an overall increase in AE rates or serious AEs compared to obese subjects receiving placebo. However, higher rates of nausea, vomiting and diarrhoea were observed in obese patients. None of these gastrointestinal events in obese patients were serious. No dose adjustment is recommended for underweight or obese subjects.

Transitioning from intravenous to subcutaneous administration

SLE

Patients with SLE transitioning from 10 mg/kg intravenously every 4 weeks to 200 mg subcutaneously weekly using a 1 to 4 week switching interval had pre-dose belimumab serum concentrations at their first subcutaneous dose close to their eventual subcutaneous steady-state trough concentration (see section 4.2). Based on simulations with population PK parameters the steady-state average belimumab concentrations for 200 mg subcutaneous every week were similar to 10 mg/kg intravenous every 4 weeks.

Lupus nephritis

One to 2 weeks after completing the first 2 intravenous doses, patients with lupus nephritis transitioning from 10 mg/kg intravenously to 200 mg subcutaneously weekly, are predicted to have average belimumab serum concentrations similar to patients dosed with 10 mg/kg intravenously every 4 weeks based on population PK simulations (see section 4.2).

Preclinical safety data

Non-clinical data reveal no special hazard for humans based on studies of repeated dose toxicity and toxicity to reproduction.

Intravenous and subcutaneous administration to monkeys resulted in the expected reduction in the number of peripheral and lymphoid tissue B cell counts with no associated toxicological findings.

Reproductive studies have been performed in pregnant cynomolgus monkeys receiving belimumab 150 mg/kg by intravenous infusion (approximately 9 times the anticipated maximum human clinical exposure) every 2 weeks for up to 21 weeks, and belimumab treatment was not associated with direct or indirect harmful effects with respect to maternal toxicity, developmental toxicity, or teratogenicity.

Treatment-related findings were limited to the expected reversible reduction of B cells in both dams and infants and reversible reduction of IgM in infant monkeys. B cell numbers recovered after the cessation of belimumab treatment by about 1 year post-partum in adult monkeys and by 3 months of life in infant monkeys; IgM levels in infants exposed to belimumab in utero recovered by 6 months of age.

Effects on male and female fertility in monkeys were assessed in the 6-month repeat dose toxicology studies of belimumab at doses up to and including 50 mg/kg. No treatment-related changes were noted in the male and female reproductive organs of sexually mature animals. An informal assessment of menstrual cycling in females demonstrated no belimumab-related changes.

As belimumab is a monoclonal antibody no genotoxicity studies have been conducted. No carcinogenicity studies or fertility studies (male or female) have been performed.

© All content on this website, including data entry, data processing, decision support tools, "RxReasoner" logo and graphics, is the intellectual property of RxReasoner and is protected by copyright laws. Unauthorized reproduction or distribution of any part of this content without explicit written permission from RxReasoner is strictly prohibited. Any third-party content used on this site is acknowledged and utilized under fair use principles.