VOTUBIA Dispersible tablet Ref.[8236] Active ingredients: Everolimus

Source: European Medicines Agency (EU) Revision Year: 2022 Publisher: Novartis Europharm Limited, Vista Building, Elm Park, Merrion Road, Dublin 4, Ireland

Pharmacodynamic properties

Pharmacotherapeutic group: Antineoplastic agents, other antineoplastic agents, protein kinase inhibitors

ATC code: L01EG02

Mechanism of action

Everolimus is a selective mTOR (mammalian target of rapamycin) inhibitor. mTOR is a key serine-threonine kinase, the activity of which is known to be upregulated in a number of human cancers. Everolimus binds to the intracellular protein FKBP-12, forming a complex that inhibits mTOR complex-1 (mTORC1) activity. Inhibition of the mTORC1 signalling pathway interferes with the translation and synthesis of proteins by reducing the activity of S6 ribosomal protein kinase (S6K1) and eukaryotic elongation factor 4E-binding protein (4EBP-1) that regulate proteins involved in the cell cycle, angiogenesis and glycolysis. Everolimus can reduce levels of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF). In patients with TSC, treatment with everolimus increases VEGF-A and decreases VEGF-D levels. Everolimus is a potent inhibitor of the growth and proliferation of tumour cells, endothelial cells, fibroblasts and blood-vessel-associated smooth muscle cells and has been shown to reduce glycolysis in solid tumours in vitro and in vivo.

Two primary regulators of mTORC1 signalling are the oncogene suppressors tuberin-sclerosis complexes 1 & 2 (TSC1, TSC2). Loss of either TSC1 or TSC2 leads to elevated rheb-GTP levels, a ras family GTPase, which interacts with the mTORC1 complex to cause its activation. mTORC1 activation leads to a downstream kinase signalling cascade, including activation of the S6 kinases. In TSC syndrome, inactivating mutations in the TSC1 or the TSC2 gene lead to hamartoma formation throughout the body. Besides pathological changes in brain tissue (such as cortical tubers) which may cause seizures, the mTOR pathway is also implicated in the pathogenesis of epilepsy in TSC. The mTOR regulates protein synthesis and multiple downstream cellular functions that may influence neuronal excitability and epileptogenesis. Overactivation of mTOR results in neuronal dysplasia, aberrant axonogenesis and dendrite formation, increased excitatory synaptic currents, reduced myelination, and disruption of the cortical laminar structure causing abnormalities in neuronal development and function. Preclinical studies in models of mTOR dysregulation in the brain demonstrated that treatment with an mTOR inhibitor such as everolimus could prolong survival, suppress seizures, prevent the development of new-onset seizures and prevent premature death. In summary, everolimus is highly active in this neuronal model of TSC, with benefit apparently attributable to effects on mTORC1 inhibition. However, the exact mechanism of action in the reduction of seizures associated with TSC is not fully elucidated.

Clinical efficacy and safety

Phase III study in patients with TSC and refractory seizures

EXIST-3 (Study CRAD001M2304), a randomised, double-blind, multicentre, three-arm, parallel-group phase III study of Votubia versus placebo as adjunctive therapy was conducted in TSC patients with refractory partial-onset seizures. In the study, partial-onset seizures were defined as all electroencephalogram (EEG)-confirmed sensory seizures or motor seizures in which a generalised onset had not been demonstrated on a past EEG. Patients were treated with concomitant and stable dose of 1 to 3 antiepileptics prior to study entry. The study consisted of three phases: an 8-week baseline observation phase; an 18-week double-blind, placebo-controlled core treatment phase (composed of titration and maintenance periods), an extension phase of ≥48 weeks in which all patients received Votubia and a post-extension phase of ≤48 weeks in which all patients received Votubia.

The study independently tested two different primary endpoints: 1) response rate defined as at least a 50% reduction from baseline in frequency of partial-onset seizures during the maintenance period of the core phase; and 2) percentage reduction from baseline in frequency of partial-onset seizures during the maintenance period of the core phase.

Secondary endpoints included seizure freedom, proportion of patients with >25% seizure frequency reduction from baseline, distribution of reduction from baseline in seizure frequency (≤-25%, >-25% to <25%; ≥25% to <50%; ≥50% to <75%; ≥75% to <100%; 100%), long-term evaluation of seizure frequency and overall quality of life.

A total of 366 patients were randomised in a 1:1.09:1 ratio to Votubia (n=117) low trough (LT) range (3 to 7 ng/ml), Votubia (n=130) high trough (HT) range (9 to 15 ng/ml) or placebo (n=119). The median age for the total population was 10.1 years (range: 2.2-56.3; 28.4% <6 years, 30.9% 6 to <12 years, 22.4% 12 to <18 years and 18.3% >18 years). Median duration of treatment was 18 weeks for all three arms in the core phase and 90 weeks (21 months) when considering both the core and extension phases.

At baseline, 19.4% of patients had focal seizures with retained awareness (sensory previously confirmed on EEG or motor), 45.1% had focal seizures with impaired awareness (predominantly non-motor), 69.1% had focal motor seizures (i.e. focal motor seizures with impaired awareness and/or secondary generalised seizures), and 1.6% had generalised onset seizures (previously confirmed by EEG). The median baseline seizure frequency across the treatment arms was 35, 38, and 42 seizures per 28 days for the Votubia LT, Votubia HT, and placebo groups, respectively. The majority of patients (67%) failed 5 or more antiepileptics prior to the study and 41.0% and 47.8% of patients were taking 2 and ≥3 antiepileptics during the study. The baseline data indicated mild to moderate mental retardation in patients 6-18 years of age (scores of 60-70 on the Adaptive Behavior Composite and Communication, Daily Living Skills, and Socialization Domain Scores).

The efficacy results for the primary endpoint are summarised in Table 5.

Table 5. EXIST-3 – Seizure frequency response rate (primary endpoint):

| Votubia | Placebo | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| LT target of 3-7 ng/ml | HT target of 9-15 ng/ml | ||

| Statistic | N=117 | N=130 | N=119 |

| Responders – n (%) | 33 (28.2) | 52 (40.0) | 18 (15.1) |

| Response rate 95% CIa | 20.3, 37.3 | 31.5, 49.0 | 9.2, 22.8 |

| Odds ratio (versus placebo)b | 2.21 | 3.93 | |

| 95% CI | 1.16, 4.20 | 2.10, 7.32 | |

| p-value (versus placebo)c | 0.008 | <0.001 | |

| Statistically significant per Bonferroni-Holm procedured | Yes | Yes | |

| Non-responders – n (%) | 84 (71.8) | 78 (60.0) | 101 (84.9) |

a Exact 95% CI obtained using Clopper-Pearson method

b Odds ratio and its 95% CI obtained using logistic regression stratified by age subgroup. Odds ratio >1 favours everolimus arm.

c p-values computed from the Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel test stratified by age subgroup

d Family-wise error rate of 2.5% one-sided

Consistent results were found for the supportive analysis of the median percentage reduction from baseline in seizure frequency (other primary endpoint): 29.3% (95% CI: 18.8, 41.9) in the Votubia LT arm, 39.6% (95% CI: 35.0, 48.7) in the Votubia HT arm and 14.9% (95% CI: 0.1, 21.7) in the placebo arm. The p-values for superiority versus placebo were 0.003 (LT) and <0.001 (HT).

The seizure-free rate (the proportion of patients who became seizure-free during the maintenance period of the core phase) was 5.1% (95% CI: 1.9, 10.8) and 3.8% (95% CI: 1.3, 8.7) in the Votubia LT and HT arms, respectively, versus 0.8% (95% CI: 0.0, 4.6) of patients in the placebo arm.

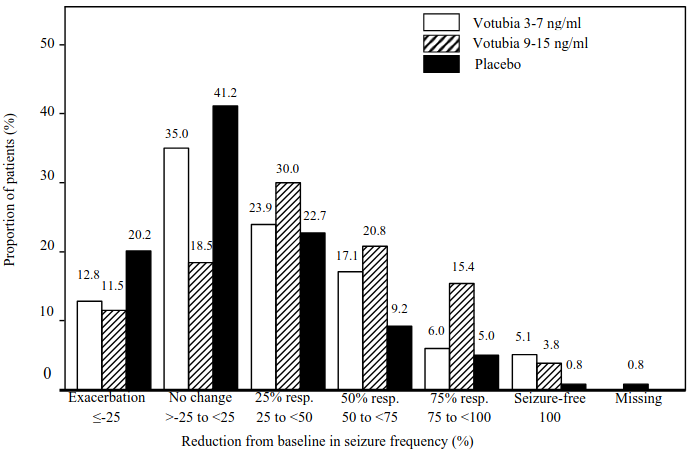

Higher proportions of responders were evident for all response categories in the Votubia LT and HT arms relative to placebo (Figure 1). Furthermore, almost twice as many patients in the placebo arm experienced seizure exacerbation relative to the Votubia LT and HT arms.

Figure 1. EXIST-3 – Distribution of reduction from baseline in seizure frequency:

A homogeneous and consistent everolimus effect was observed across all subgroups evaluated for the primary efficacy endpoints by: age categories (Table 6), gender, race and ethnicity, seizure types, seizure frequency at baseline, number and name of concomitant antiepileptics, and TSC features (angiomyolipoma, SEGA, cortical tuber status). The effect of everolimus on infantile/epileptic spasms or on seizures associated with Lennox-Gastaut syndrome has not been studied and is not established for generalised-onset seizures and subjects without cortical tubers.

Table 6. EXIST-3 – Seizure frequency response rate by age:

| Votubia | Placebo | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| LT target of 3-7 ng/ml | HT target of 9-15 ng/ml | ||

| Age category | N=117 | N=130 | N=119 |

| <6 years | n=33 | n=37 | n=34 |

| Response rate (95% CI)a | 30.3 (15.6, 48.7) | 59.5 (42.1, 75.2) | 17.6 (6.8, 34.5) |

| 6 to <12 years | n=37 | n=39 | n=37 |

| Response rate (95% CI)a | 29.7 (15.9, 47.0) | 28.2 (15.0, 44.9) | 10.8 (3.0, 25.4) |

| 12 to <18 years | n=26 | n=31 | n=25 |

| Response rate (95% CI)a | 23.1 (9.0, 43.6) | 32.3 (16.7, 51.4) | 16.0 (4.5, 36.1) |

| ≥18 yearsb | n=21 | n=23 | n=23 |

| Response rate (95% CI)a | 28.6 (11.3, 52.2) | 39.1 (19.7, 61.5) | 17.4 (5.0, 38.8) |

a Exact 95% CI obtained using Clopper-Pearson method

b No efficacy data available in elderly patients

At the end of the core phase, overall quality of life in patients aged 2 to <11 years (as measured by the mean change from baseline in overall Quality Of Life score [total score] in the Childhood Epilepsy Questionnaire [QOLCE]) was maintained in each Votubia treatment arm as well as in the placebo arm.

Reduction in seizure frequency was sustained over an evaluation period of approximately 2 years. Based on a sensitivity analysis considering patients who prematurely discontinued everolimus as non-responders, response rates of 38.4% (95% CI: 33.4, 43.7) and 44.4% (95% CI: 38.2, 50.7) were observed after 1 and 2 years of exposure to everolimus, respectively.

Phase III study in SEGA patients

EXIST-1 (Study CRAD001M2301), a randomised, double-blind, multicentre phase III study of Votubia versus placebo, was conducted in patients with SEGA, irrespective of age. Patients were randomised in a 2:1 ratio to receive either Votubia or matching placebo. Presence of at least one SEGA lesion ≥1.0 cm in longest diameter using MRI (based on local radiology assessment) was required for entry. In addition, serial radiological evidence of SEGA growth, presence of a new SEGA lesion ≥1 cm in longest diameter, or new or worsening hydrocephalus was required for entry.

The primary efficacy endpoint was SEGA response rate based on independent central radiology review. The analysis was stratified by use of enzyme-inducing antiepileptics at randomisation (yes/no).

Key secondary endpoints in hierarchal order of testing included the absolute change in frequency of total seizure events per 24-hour EEG from baseline to week 24, time to SEGA progression, and skin lesion response rate.

A total of 117 patients were randomised, 78 to Votubia and 39 to placebo. The two treatment arms were generally well balanced with respect to demographic and baseline disease characteristics and history of prior anti-SEGA therapies. In the total population, 57.3% of patients were male and 93.2% were Caucasian. The median age for the total population was 9.5 years (age range for the Votubia arm: 1.0 to 23.9; age range for the placebo arm: 0.8 to 26.6), 69.2% of the patients were aged 3 to <18 years and 17.1% were <3 years at enrolment.

Of the enrolled patients, 79.5% had bilateral SEGAs, 42.7% had ≥2 target SEGA lesions, 25.6% had inferior growth, 9.4% had evidence of deep parenchymal invasion, 6.8% had radiographic evidence of hydrocephalus, and 6.8% had undergone prior SEGA-related surgery. 94.0% had skin lesions at baseline and 37.6% had target renal angiomyolipoma lesions (at least one angiomyolipoma ≥1 cm in longest diameter).

The median duration of blinded study treatment was 9.6 months (range: 5.5 to 18.1) for patients receiving Votubia and 8.3 months (range: 3.2 to 18.3) for those receiving placebo.

Results showed that Votubia was superior to placebo for the primary endpoint of best overall SEGA response (p<0.0001). Response rates were 34.6% (95% CI: 24.2, 46.2) for the Votubia arm compared with 0% (95% CI: 0.0, 9.0) for the placebo arm (Table 7). In addition, all 8 patients on the Votubia arm who had radiographic evidence of hydrocephalus at baseline had a decrease in ventricular volume.

Patients initially treated with placebo were allowed to cross over to everolimus at the time of SEGA progression and upon recognition that treatment with everolimus was superior to treatment with placebo. All patients receiving at least one dose of everolimus were followed until medicinal product discontinuation or study completion. At the time of the final analysis, the median duration of exposure among all such patients was 204.9 weeks (range: 8.1 to 253.7). The best overall SEGA response rate had increased to 57.7% (95% CI: 47.9, 67.0) at the final analysis.

No patient required surgical intervention for SEGA during the entire course of the study.

Table 7. EXIST-1 – SEGA response:

| Primary analysis3 | Final analysis4 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Votubia | Placebo | p-value | Votubia | |

| N=78 | N=39 | N=111 | ||

| SEGA response rate1,2 - (%) | 34.6 | 0 | <0.0001 | 57.7 |

| 95% CI | 24.2, 46.2 | 0.0, 9.0 | 47.9, 67.0 | |

| Best overall SEGA response - (%) | ||||

| Response | 34.6 | 0 | 57.7 | |

| Stable disease | 62.8 | 92.3 | 39.6 | |

| Progression | 0 | 7.7 | 0 | |

| Not evaluable | 2.6 | 0 | 2.7 | |

1 according to independent central radiology review.

2 SEGA responses were confirmed with a repeat scan. Response was defined as: ≥50% reduction in the sum of SEGA volume relative to baseline, plus no unequivocal worsening of non-target SEGA lesions, plus absence of new SEGA ≥1 cm in longest diameter, plus no new or worsening hydrocephalus.

3 Primary analysis for double blind period.

4 Final analysis includes patients who crossed over from the placebo group; median duration of exposure to everolimus of 204.9 weeks.

Consistent treatment effects were observed across all subgroups evaluated (i.e. enzyme-inducing antiepileptic use versus enzyme-inducing antiepileptic non-use, sex and age) at the primary analysis.

During the double-blind period, reduction of SEGA volume was evident within the initial 12 weeks of Votubia treatment: 29.7% (22/74) of patients had ≥50% reductions in volume and 73.0% (54/74) had ≥30% reductions in volume. Sustained reductions were evident at week 24, 41.9% (31/74) of patients had ≥50% reductions and 78.4% (58/74) of patients had ≥30% reductions in SEGA volume.

In the everolimus treated population (N=111) of the study, including patients who crossed over from the placebo group, tumour response, starting as early as after 12 weeks on everolimus, was sustained at later time points. The proportion of patients achieving at least 50% reductions in SEGA volume was 45.9% (45/98) and 62.1% (41/66) at weeks 96 and 192 after start of everolimus treatment. Similarly, the proportion of patients achieving at least 30% reductions in SEGA volume was 71.4% (70/98) and 77.3% (51/66) at weeks 96 and 192 after start of everolimus treatment.

Analysis of the first key secondary endpoint, change in seizure frequency, was inconclusive; thus, despite the fact that positive results were observed for the two subsequent secondary endpoints (time to SEGA progression and skin lesion response rate), they could not be declared formally statistically significant.

Median time to SEGA progression based on central radiology review was not reached in either treatment arm. Progressions were only observed in the placebo arm (15.4%; p=0.0002). Estimated progression-free rates at 6 months were 100% for the Votubia arm and 85.7% for the placebo arm. The long-term follow-up of patients randomised to everolimus and patients randomised to placebo who thereafter crossed over to everolimus demonstrated durable responses.

At the time of the primary analysis, Votubia demonstrated clinically meaningful improvements in skin lesion response (p=0.0004), with response rates of 41.7% (95% CI: 30.2, 53.9) for the Votubia arm and 10.5% (95% CI: 2.9, 24.8) for the placebo arm. At the final analysis, the skin lesion response rate increased to 58.1% (95% CI: 48.1, 67.7).

Phase II study in patients with SEGA

A prospective, open-label, single-arm phase II study (Study CRAD001C2485) was conducted to evaluate the safety and efficacy of Votubia in patients with SEGA. Radiological evidence of serial SEGA growth was required for entry.

Change in SEGA volume during the core 6-month treatment phase, as assessed via an independent central radiology review, was the primary efficacy endpoint. After the core treatment phase, patients could be enrolled into an extension phase where SEGA volume was assessed every 6 months.

In total, 28 patients received treatment with Votubia; median age was 11 years (range 3 to 34), 61% male, 86% Caucasian. Thirteen patients (46%) had a secondary smaller SEGA, including 12 in the contralateral ventricle.

Primary SEGA volume was reduced at month 6 compared to baseline (p<0.001 [see Table 8]). No patient developed new lesions, worsening hydrocephalus or increased intracranial pressure, and none required surgical resection or other therapy for SEGA.

Table 8. Change in primary SEGA volume over time:

| SEGA volume (cm³) | Independent central review | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline n=28 | Month 6 n=27 | Month 12 n=26 | Month 24 n=24 | Month 36 n=23 | Month 48 n=24 | Month 60 n=23 | |

| Primary tumour volume | |||||||

| Mean (standard deviation) | 2.45 (2.813) | 1.33 (1.497) | 1.26 (1.526) | 1.19 (1.042) | 1.26 (1.298) | 1.16 (0.961) | 1.24 (0.959) |

| Median | 1.74 | 0.93 | 0.84 | 0.94 | 1.12 | 1.02 | 1.17 |

| Range | 0.49 – 14.23 | 0.31 – 7.98 | 0.29 – 8.18 | 0.20 – 4.63 | 0.22 – 6.52 | 0.18 – 4.19 | 0.21 – 4.39 |

| Reduction from baseline | |||||||

| Mean (standard deviation) | 1.19 (1.433) | 1.07 (1.276) | 1.25 (1.994) | 1.41 (1.814) | 1.43 (2.267) | 1.44 (2.230) | |

| Median | 0.83 | 0.85 | 0.71 | 0.71 | 0.83 | 0.50 | |

| Range | 0.06 – 6.25 | 0.02 – 6.05 | -0.55 – 9.60 | 0.15 – 7.71 | 0.00 – 10.96 | -0.74 – 9.84 | |

| Percentage reduction from baseline, n (%) | |||||||

| ≥50% | 9 (33.3) | 9 (34.6) | 12 (50.0) | 10 (43.5) | 14 (58.3) | 12 (52.2) | |

| ≥30% | 21 (77.8) | 20 (76.9) | 19 (79.2) | 18 (78.3) | 19 (79.2) | 14 (60.9) | |

| >0% | 27 (100.0) | 26 (100.0) | 23 (95.8) | 23 (100.0) | 23 (95.8) | 21 (91.3) | |

| No change | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (4.2) | 0 | |

| Increase | 0 | 0 | 1 (4.2) | 0 | 0 | 2 (8.7) | |

The robustness and consistency of the primary analysis were supported by the:

- change in primary SEGA volume as per local investigator assessment (p<0.001), with 75.0% and 39.3% of patients experiencing reductions of ≥30% and ≥50%, respectively

- change in total SEGA volume as per independent central review (p<0.001) or local investigator assessment (p<0.001).

One patient met the pre-specified criteria for treatment success (>75% reduction in SEGA volume) and was temporarily taken off trial therapy; however, SEGA re-growth was evident at the next assessment at 4.5 months and treatment was restarted.

Long-term follow-up to a median duration of 67.8 months (range: 4.7 to 83.2) demonstrated sustained efficacy.

Other studies

Stomatitis is the most commonly reported adverse reaction in patients treated with Votubia (see sections 4.4 and 4.8). In a post-marketing single-arm study in postmenopausal women with advanced breast cancer (N=92), topical treatment with dexamethasone 0.5 mg/5 ml alcohol-free oral solution was administered as a mouthwash (4 times daily for the initial 8 weeks of treatment) to patients at the time of initiating treatment with Afinitor (everolimus, 10 mg/day) plus exemestane (25 mg/day) to reduce the incidence and severity of stomatitis. The incidence of Grade ≥2 stomatitis at 8 weeks was 2.4% (n=2/85 evaluable patients) which was lower than historically reported. The incidence of Grade 1 stomatitis was 18.8% (n=16/85) and no cases of Grade 3 or 4 stomatitis were reported. The overall safety profile in this study was consistent with that established for everolimus in the oncology and TSC settings, with the exception of a slightly increased frequency of oral candidiasis which was reported in 2.2% (n=2/92) of patients.

Paediatric population

The European Medicines Agency has waived the obligation to submit the results of studies with Votubia in all subsets of the paediatric population in angiomyolipoma (see section 4.2 for information on paediatric use).

The marketing authorisation holder has completed the Paediatric Investigation Plans for Votubia for refractory seizures associated with TSC. This summary of product characteristics has been updated to include the results of studies with Votubia in the paediatric population (see section 5.2).

Pharmacokinetic properties

Absorption

In patients with advanced solid tumours, peak everolimus concentrations (Cmax) are reached at a median time of 1 hour after daily administration of 5 and 10 mg everolimus under fasting conditions or with a light fat-free snack. Cmax is dose-proportional between 5 and 10 mg. Everolimus is a substrate and moderate inhibitor of PgP.

Food effect

In healthy subjects, high fat meals reduced systemic exposure to Votubia 10 mg tablets (as measured by AUC) by 22% and the peak blood concentration Cmax by 54%. Light fat meals reduced AUC by 32% and Cmax by 42%.

In healthy subjects taking a single 9 mg dose (3 × 3 mg) of Votubia dispersible tablets in suspension, high fat meals reduced AUC by 11.7% and the peak blood concentration Cmax by 59.8%. Light fat meals reduced AUC by 29.5% and Cmax by 50.2%.

Food, however, had no apparent effect on the post absorption phase concentration-time profile 24 hours post-dose of either dosage form.

Relative bioavailability/bioequivalence

In a relative bioavailability study, AUC0-inf of 5 × 1 mg everolimus tablets when administered as suspension in water was equivalent to 5 × 1 mg everolimus tablets administered as intact tablets, and Cmax of 5 × 1 mg everolimus tablets in suspension was 72% of 5 × 1 mg intact everolimus tablets.

In a bioequivalence study, AUC0-inf of the 5 mg dispersible tablet when administered as suspension in water was equivalent to 5 × 1 mg intact everolimus tablets, and Cmax of the 5 mg dispersible tablet in suspension was 64% of 5 × 1 mg intact everolimus tablets.

Distribution

The blood-to-plasma ratio of everolimus, which is concentration-dependent over the range of 5 to 5,000 ng/ml, is 17% to 73%. Approximately 20% of the everolimus concentration in whole blood is confined to plasma of cancer patients given Votubia 10 mg/day. Plasma protein binding is approximately 74% both in healthy subjects and in patients with moderate hepatic impairment. In patients with advanced solid tumours, Vd was 191 l for the apparent central compartment and 517 l for the apparent peripheral compartment.

Nonclinical studies in rats indicate:

- A rapid uptake of everolimus in the brain followed by a slow efflux.

- The radioactive metabolites of [3H]everolimus do not significantly cross the blood-brain barrier.

- A dose-dependent brain penetration of everolimus, which is consistent with the hypothesis of saturation of an efflux pump present in the brain capillary endothelial cells.

- The co-administration of the PgP inhibitor, cyclosporine, enhances the exposure of everolimus in the brain cortex, which is consistent with the inhibition of PgP at the blood-brain barrier.

There are no clinical data on the distribution of everolimus in the human brain. Non-clinical studies in rats demonstrated distribution into the brain following administration by both the intravenous and oral routes.

Biotransformation

Everolimus is a substrate of CYP3A4 and PgP. Following oral administration, everolimus is the main circulating component in human blood. Six main metabolites of everolimus have been detected in human blood, including three monohydroxylated metabolites, two hydrolytic ring-opened products, and a phosphatidylcholine conjugate of everolimus. These metabolites were also identified in animal species used in toxicity studies and showed approximately 100 times less activity than everolimus itself. Hence, everolimus is considered to contribute the majority of the overall pharmacological activity.

Elimination

Mean CL/F of everolimus after 10 mg daily dose in patients with advanced solid tumours was 24.5 l/h. The mean elimination half-life of everolimus is approximately 30 hours.

No specific excretion studies have been undertaken in cancer patients; however, data are available from the studies in transplant patients. Following the administration of a single dose of radiolabelled everolimus in conjunction with ciclosporin, 80% of the radioactivity was recovered from the faeces, while 5% was excreted in the urine. The parent substance was not detected in urine or faeces.

Steady-state pharmacokinetics

After administration of everolimus in patients with advanced solid tumours, steady-state AUC0-τ was dose-proportional over the range of 5 to 10 mg daily dose. Steady-state was achieved within 2 weeks. Cmax is dose-proportional between 5 and 10 mg. tmax occurs at 1 to 2 hours post-dose. There was a significant correlation between AUC0-τ and pre-dose trough concentration at steady-state.

Special populations

Hepatic impairment

The safety, tolerability and pharmacokinetics of Votubia were evaluated in two single oral dose studies of Votubia tablets in 8 and 34 adult subjects with impaired hepatic function relative to subjects with normal hepatic function.

In the first study, the average AUC of everolimus in 8 subjects with moderate hepatic impairment (Child-Pugh B) was twice that found in 8 subjects with normal hepatic function.

In the second study of 34 subjects with different impaired hepatic function compared to normal subjects, there was a 1.6-fold, 3.3-fold and 3.6-fold increase in exposure (i.e. AUC0-inf) for subjects with mild (Child-Pugh A), moderate (Child-Pugh B) and severe (Child-Pugh C) hepatic impairment, respectively.

Simulations of multiple dose pharmacokinetics support the dosing recommendations in subjects with hepatic impairment based on their Child-Pugh status.

Based on the results of the two studies, dose adjustment is recommended for patients with hepatic impairment (see sections 4.2 and 4.4).

Renal impairment

In a population pharmacokinetic analysis of 170 patients with advanced solid tumours, no significant influence of creatinine clearance (25-178 ml/min) was detected on CL/F of everolimus. Post-transplant renal impairment (creatinine clearance range 11-107 ml/min) did not affect the pharmacokinetics of everolimus in transplant patients.

Paediatric population

In patients with SEGA, everolimus Cmin was approximately dose-proportional within the dose range from 1.35 mg/m² to 14.4 mg/m².

In patients with SEGA, the geometric mean Cmin values normalised to mg/m² dose in patients aged <10 years and 10-18 years were lower by 54% and 40%, respectively, than those observed in adults (>18 years of age), suggesting that everolimus clearance was higher in younger patients. Limited data in patients <3 years of age (n=13) indicate that BSA-normalised clearance is about two-fold higher in patients with low BSA (BSA of 0.556 m²) than in adults. Therefore it is assumed that steady-state could be reached earlier in patients <3 years of age (see section 4.2 for dosing recommendations).

The pharmacokinetics of everolimus have not been studied in patients younger than 1 year of age. It is reported, however, that CYP3A4 activity is reduced at birth and increases during the first year of life, which could affect the clearance in this patient population.

A population pharmacokinetic analysis including 111 patients with SEGA who ranged from 1.0 to 27.4 years (including 18 patients 1 to less than 3 years of age with BSA 0.42 m² to 0.74 m²) showed that BSA-normalised clearance is in general higher in younger patients. Population pharmacokinetic model simulations showed that a starting dose of 7 mg/m² would be necessary to attain Cmin within the 5 to 15 ng/ml range in patients younger than 3 years of age. A higher starting dose of 7 mg/m² is therefore recommended for patients 1 to less than 3 years of age with SEGA (see section 4.2).

In patients with TSC and refractory seizures receiving Votubia dispersible tablets, a trend was observed toward lower Cmin normalised to dose (as mg/m²) in younger patients. Median Cmin normalised to mg/m² dose was lower for the younger age groups, indicating that everolimus clearance (normalised to BSA) was higher in younger patients.

In patients with TSC and refractory seizures Votubia concentrations were investigated in 9 patients in the age between 1 and <2 years. Doses of 6 mg/m² (absolute doses range 1-5 mg) were administered and resulted in minimal concentrations between 2 and 10 ng/ml (median of 5 ng/ml; total of >50 measurements). No data are available in patients with TSC-seizures below the age of 1 year.

Elderly

In a population pharmacokinetic evaluation in cancer patients, no significant influence of age (27-85 years) on oral clearance of everolimus was detected.

Ethnicity

Oral clearance (CL/F) is similar in Japanese and Caucasian cancer patients with similar liver functions. Based on analysis of population pharmacokinetics, oral clearance (CL/F) is on average 20% higher in black transplant patients.

Pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic relationship(s)

In patients with TSC and refractory seizures, a conditional logistic regression analysis based on the core phase of Study CRAD001M2304 to estimate the probability of seizure response versus Time Normalised (TN)-Cmin stratified by age sub-group, indicated that a 2-fold increase in TN-Cmin was associated with a 2.172-fold increase (95% CI: 1.339, 3.524) in the odds for a seizure response over the observed TN-Cmin ranges of 0.97 ng/ml to 16.40 ng/ml. Baseline seizure frequency was a significant factor in the seizure response (with an odds ratio of 0.978 [95% CI: 0.959, 0.998]). This outcome was consistent with the results of a linear regression model predicting the log of absolute seizure frequency during the maintenance period of the core phase, which indicated that for a 2-fold increase in TN-Cmin there was a statistically significant 28% reduction (95% CI: 12%, 42%) in absolute seizure frequency. Baseline seizure frequency and TN-Cmin were both significant factors (α=0.05) in predicting the absolute seizure frequency in the linear regression model.

Preclinical safety data

The non-clinical safety profile of everolimus was assessed in mice, rats, minipigs, monkeys and rabbits. The major target organs were male and female reproductive systems (testicular tubular degeneration, reduced sperm content in epididymides and uterine atrophy) in several species; lungs (increased alveolar macrophages) in rats and mice; pancreas (degranulation and vacuolation of exocrine cells in monkeys and minipigs, respectively, and degeneration of islet cells in monkeys), and eyes (lenticular anterior suture line opacities) in rats only. Minor kidney changes were seen in the rat (exacerbation of age-related lipofuscin in tubular epithelium, increases in hydronephrosis) and mouse (exacerbation of background lesions). There was no indication of kidney toxicity in monkeys or minipigs.

Everolimus appeared to spontaneously exacerbate background diseases (chronic myocarditis in rats, coxsackie virus infection of plasma and heart in monkeys, coccidian infestation of the gastrointestinal tract in minipigs, skin lesions in mice and monkeys). These findings were generally observed at systemic exposure levels within the range of therapeutic exposure or above, with the exception of the findings in rats, which occurred below therapeutic exposure due to a high tissue distribution.

In a male fertility study in rats, testicular morphology was affected at 0.5 mg/kg and above, and sperm motility, sperm head count, and plasma testosterone levels were diminished at 5 mg/kg, which is within the range of therapeutic exposure and which caused a reduction in male fertility. There was evidence of reversibility.

In animal reproductive studies female fertility was not affected. However, oral doses of everolimus in female rats at ≥0.1 mg/kg (approximately 4% of the AUC0-24h in patients receiving the 10 mg daily dose) resulted in increases in pre-implantation loss.

Everolimus crossed the placenta and was toxic to the foetus. In rats, everolimus caused embryo/foetotoxicity at systemic exposure below the therapeutic level. This was manifested as mortality and reduced foetal weight. The incidence of skeletal variations and malformations (e.g. sternal cleft) was increased at 0.3 and 0.9 mg/kg. In rabbits, embryotoxicity was evident in an increase in late resorptions.

In juvenile rat toxicity studies, systemic toxicity included decreased body weight gain, food consumption, and delayed attainment of some developmental landmarks, with full or partial recovery after cessation of dosing. With the possible exception of the rat-specific lens finding (where young animals appeared to be more susceptible), it appears that there is no significant difference in the sensitivity of juvenile animals to the adverse reactions of everolimus as compared to adult animals. Toxicity study with juvenile monkeys did not show any relevant toxicity.

Genotoxicity studies covering relevant genotoxicity endpoints showed no evidence of clastogenic or mutagenic activity. Administration of everolimus for up to 2 years did not indicate any oncogenic potential in mice and rats up to the highest doses, corresponding respectively to 4.3 and 0.2 times the estimated clinical exposure.

© All content on this website, including data entry, data processing, decision support tools, "RxReasoner" logo and graphics, is the intellectual property of RxReasoner and is protected by copyright laws. Unauthorized reproduction or distribution of any part of this content without explicit written permission from RxReasoner is strictly prohibited. Any third-party content used on this site is acknowledged and utilized under fair use principles.