LENVIMA Hard capsule Ref.[9037] Active ingredients: Lenvatinib

Source: European Medicines Agency (EU) Revision Year: 2024 Publisher: Eisai GmbH, Edmund-Rumpler-Straße 3,60549 Frankfurt am Main, Germany, E-mail: medinfo_de@eisai.net

Pharmacodynamic properties

Pharmacotherapeutic group: antineoplastic agents, protein kinase inhibitors

ATC code: L01EX08

Lenvatinib is a multikinase inhibitor which has shown mainly antiangiogenic properties in vitro and in vivo, and direct inhibition of tumour growth was also observed in in vitro models.

Mechanism of action

Lenvatinib is a receptor tyrosine kinase (RTK) inhibitor that selectively inhibits the kinase activities of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) receptors VEGFR1 (FLT1), VEGFR2 (KDR), and VEGFR3 (FLT4), in addition to other proangiogenic and oncogenic pathway-related RTKs including fibroblast growth factor (FGF) receptors FGFR1, 2, 3, and 4, the platelet derived growth factor (PDGF) receptor PDGFRα, KIT, and RET.

In addition, lenvatinib had selective, direct antiproliferative activity in hepatocellular cell lines dependent on activated FGFR signalling, which is attributed to the inhibition of FGFR signalling by lenvatinib.

In syngeneic mouse tumour models, lenvatinib decreased tumour-associated macrophages, increased activated cytotoxic T cells, and demonstrated greater antitumour activity in combination with an anti-PD-1 monoclonal antibody compared to either treatment alone.

Although not studied directly with lenvatinib, the mechanism of action (MOA) for hypertension is postulated to be mediated by the inhibition of VEGFR2 in vascular endothelial cells. Similarly, although not studied directly, the MOA for proteinuria is postulated to be mediated by downregulation of VEGFR1 and VEGFR2 in the podocytes of the glomerulus.

The mechanism of action for hypothyroidism is not fully elucidated.

Clinical efficacy

Radioiodine-refractory differentiated thyroid cancer

The SELECT study was a multicentre, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial that was conducted in 392 patients with radioiodine-refractory differentiated thyroid cancer with independent, centrally reviewed, radiographic evidence of disease progression within 12 months (+1 month window) prior to enrolment. Radioiodine-refractory was defined as one or more measurable lesions either with a lack of iodine uptake or with progression in spite of radioactive-iodine (RAI) therapy, or 30 having a cumulative activity of RAI of >600 mCi or 22 GBq with the last dose at least 6 months prior to study entry. Randomisation was stratified by geographic region (Europe, North America, and Other), prior VEGF/VEGFR-targeted therapy (patients may have received 0 or 1 prior VEGF/VEGFR-targeted therapy), and age (≤65 years or >65 years). The main efficacy outcome measure was progression-free survival (PFS) as determined by blinded independent radiologic review using Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumours (RECIST) 1.1. Secondary efficacy outcome measures included overall response rate and overall survival. Patients in the placebo arm could opt to receive lenvatinib treatment at the time of confirmed disease progression.

Eligible patients with measurable disease according to RECIST 1.1 were randomised 2:1 to receive lenvatinib 24 mg once daily (n=261) or placebo (n=131). Baseline demographics and disease characteristics were well balanced for both treatment groups. Of the 392 patients randomised, 76.3% were naïve to prior VEGF/VEGFR-targeted therapies, 49.0% were female, 49.7% were European, and the median age was 63 years. Histologically, 66.1% had a confirmed diagnosis of papillary thyroid cancer and 33.9% had follicular thyroid cancer which included Hürthle cell 14.8% and clear cell 3.8%. Metastases were present in 99% of the patients: lungs in 89.3%, lymph nodes in 51.5%, bone in 38.8%, liver in 18.1%, pleura in 16.3%, and brain in 4.1%. The majority of patients had an ECOG performance status of 0; 42.1% had a status of 1; 3.9% had a status above 1. The median cumulative RAI activity administered prior to study entry was 350 mCi (12.95 GBq).

A statistically significant prolongation in PFS was demonstrated in lenvatinib-treated patients compared with those receiving placebo (p<0.0001) (see figure 1). The positive effect on PFS was seen across the subgroups of age (above or below 65 years), sex, race, histological subtype, geographic region, and those who received 0 or 1 prior VEGF/VEGFR-targeted therapies. Following independent review confirmation of disease progression, 109 (83.2%) patients randomised to placebo had crossed over to open-label lenvatinib at the time of the primary efficacy analysis.

The objective response rate (complete response [CR] plus partial response [PR]) per independent radiological review was significantly (p<0.0001) higher in the lenvatinib-treated group (64.8%) than in the placebo-treated group (1.5%). Four (1.5%) subjects treated with lenvatinib attained a CR and 165 subjects (63.2%) had a PR, while no subjects treated with placebo had a CR and 2 (1.5%) subjects had a PR.

The median time to first dose reduction was 2.8 months. The median time to objective responsive was 2.0 (95% CI: 1.9, 3.5) months; however, of the patients who experienced a complete or partial response to lenvatinib, 70.4% were observed to develop the response on or within 30 days of being on the 24-mg dose.

The overall survival analysis was confounded by the fact that placebo-treated subjects with confirmed disease progression had the option to cross over to open-label lenvatinib. There was no statistically significant difference in overall survival between the treatment groups at the time of the primary efficacy analysis (HR=0.73; 95% CI: 0.50, 1.07, p=0.1032). The median Overall Survival (OS) had not been reached for either the lenvatinib group or the placebo crossover group.

Table 7. Efficacy results in DTC patients:

| Lenvatinib N=261 | Placebo N=131 | |

|---|---|---|

| Progression-Free Survival (PFS)a | ||

| Number of progressions or deaths (%) | 107 (41.0) | 113 (86.3) |

| Median PFS in months (95% CI) | 18.3 (15.1, NE) | 3.6 (2.2, 3.7) |

| Hazard ratio (99% CI)b,c | 0.21 (0.14, 0.31) | |

| P valueb | <0.0001 | |

| Patients who had received 0 prior | ||

| VEGF/VEGFR-targeted therapy (%) | 195 (74.7) | 104 (79.4) |

| Number of progressions or deaths | 76 | 88 |

| Median PFS in months (95% CI) | 18.7 (16.4, NE) | 3.6 (2.1, 5.3) |

| Hazard ratio (95% CI)b,c | 0.20 (0.14, 0.27) | |

| Patients who had received 1 prior VEGF/VEGFR-targeted therapy (%) | 66 (25.3) | 27 (20.6) |

| Number of progressions or deaths | 31 | 25 |

| Median PFS in months (95% CI) | 15.1 (8.8, NE) | 3.6 (1.9, 3.7) |

| Hazard ratio (95% CI)b,c | 0.22 (0.12, 0.41) | |

| Objective Response Ratea | ||

| Number of objective responders (%) | 169 (64.8) | 2 (1.5) |

| (95% CI) | (59.0, 70.5) | (0.0, 3.6) |

| P valueb | <0.0001 | |

| Number of complete responses | 4 | 0 |

| Number of partial responses | 165 | 2 |

| Median time to objective response,d months (95% CI) | 2.0 (1.9, 3.5) | 5.6 (1.8, 9.4) |

| Duration of response,d months, median (95% CI) | NE (16.8, NE) | NE (NE, NE) |

| Overall Survival | ||

| Number of deaths (%) | 71 (27.2) | 47 (35.9) |

| Median OS in months (95% CI) | NE (22.0, NE) | NE (20.3, NE) |

| Hazard ratio (95% CI)b,e | 0.73 (0.50, 1.07) | |

| P valueb,e | 0.1032 | |

CI, confidence interval; NE, not estimable; OS, overall survival; PFS, progression-free survival; RPSFT, rank preserving structural failure time model; VEGF/VEGFR, vascular endothelial growth factor/vascular endothelial growth factor receptor.

a Independent radiologic review.

b Stratified by region (Europe vs. North America vs. Other), age group (≤65 years vs >65 years), and previous VEGF/VEGFR-targeted therapy (0 vs. 1).

c Estimated with Cox proportional hazard model.

d Estimated using the Kaplan-Meier method; the 95% CI was constructed with a generalised Brookmeyer and Crowley method in patients with a best overall response of complete response or partial response.

e Not adjusted for crossover effect.

Figure 1. Kaplan-Meier Curve of Progression-Free Survival – DTC:

CI, confidence interval; NE, not estimable.

Hepatocellular carcinoma

The clinical efficacy and safety of lenvatinib have been evaluated in an international, multicenter, open-label, randomised phase 3 study (REFLECT) in patients with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC).

In total, 954 patients were randomised 1:1 to receive either lenvatinib (12 mg [baseline body weight ≥60 kg] or 8 mg [baseline body weight <60 kg]) given orally once daily or sorafenib 400 mg given orally twice daily.

Patients were eligible to participate if they had a liver function status of Child-Pugh class A and Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Performance Status (ECOG PS) 0 or 1. Patients were excluded who had prior systemic anticancer therapy for advanced/unresectable HCC or any prior anti-VEGF therapy. Target lesions previously treated with radiotherapy or locoregional therapy had to show radiographic evidence of disease progression. Patients with ≥50% liver occupation, clear invasion into the bile duct or a main branch of the portal vein (Vp4) on imaging were also excluded.

- Demographic and baseline disease characteristics were similar between the lenvatinib and the sorafenib groups and are shown below for all 954 randomised patients:

- Median age: 62 years

- Male: 84%

- White: 29%, Asian: 69%, Black or African American: 1.4%

- Body weight: <60 kg -31%, 60-80 kg – 50%, >80 kg – 19%

- Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Performance Status (ECOG PS) of 0: 63%, ECOG PS of 1: 37%

- Child-Pugh A: 99%, Child-Pugh B: 1%

- Aetiology: Hepatitis B (50%), Hepatitis C (23%), alcohol (6%)

- Absence of macroscopic portal vein invasion (MPVI): 79%

- Absence of MPVI, extra-hepatic tumour spread (EHS) or both: 30%

- Underlying cirrhosis (by independent imaging review): 75%

- Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer (BCLC) stage B: 20%; BCLC stage C: 80%

- Prior treatments: hepatectomy (28%), radiotherapy (11%), loco-regional therapies including transarterial (chemo)embolisation (52%), radiofrequency ablation (21%) and percutaneous ethanol injection (4%)

The primary efficacy endpoint was Overall Survival (OS). Lenvatinib was non-inferior for OS to sorafenib with HR = 0.92 [95% CI of (0.79, 1.06)] and a median OS of 13.6 months vs 12.3 months (see Table 8 and Figure 2). The results for surrogate endpoints (PFS and ORR) are presented in Table 8 below.

Table 8. Efficacy Results from the REFLECT study in HCC:

| Efficacy parameter | Hazard ratioa,b (95% CI) | P valued | Median (95% CI)e | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lenvatinib (N=478) | Sorafenib (N=476) | |||

| OS | 0.92 (0.79,1.06) | NA | 13.6 (12.1, 14.9) | 12.3 (10.4, 13.9) |

| PFSg (mRECIST) | 0.64 (0.55, 0.75) | <0.00001 | 7.3 (5.6, 7.5) | 3.6 (3.6, 3.7) |

| Percentages (95% CI) | ||||

| ORRc,f,g (mRECIST) | NA | <0.00001 | 41% (36%, 45%) | 12% (9%, 15%) |

Data cut-off date: 13 Nov 2016.

a Hazard ratio (HR) is for lenvatinib vs. sorafenib, based on a Cox model including treatment group as a factor.

b Stratified by region (Region 1: Asia-Pacific; Region 2: Western), macroscopic portal vein invasion or extrahepatic spread or both (yes, no), ECOG PS (0, 1) and body weight (<60 kg, ≥60 kg).

c Results are based on confirmed and unconfirmed responses.

d P-value is for the superiority test of lenvatinib versus sorafenib.

e Quartiles are estimated by the Kaplan-Meier method, and the 95% CIs are estimated with a generalised Brookmeyer and Crowley method

f Response rate (complete or partial response)

g Per independent radiology review retrospective analysis. The median duration of objective response was 7.3 (95% CI 5.6, 7.4) months in the lenvatinib arm and 6.2 (95% CI 3.7, 11.2) months in the sorafenib arm.

Figure 2. Kaplan-Meier Curve of Overall Survival – HCC:

In subgroup analyses by stratification factors (presence or absence of MPVI or EHS or both, ECOG PS 0 or 1, BW <60 kg or ≥60 kg and region) the HR consistently favoured lenvatinib over sorafenib, with the exception of Western region [HR of 1.08 (95% CI 0.82, 1.42], patients without EHS [HR of 1.01 (95% CI 0.78, 1.30)] and patients without MPVI, EHS or both [HR of 1.05 (0.79, 1.40)]. The results of subgroup analyses should be interpreted with caution.

The median duration of treatment was 5.7 months (Q1: 2.9, Q3: 11.1) in the lenvatinib arm and 3.7 months (Q1: 1.8, Q3: 7.4) in the sorafenib arm.

In both treatment arms in the REFLECT study, median OS was approximately 9 months longer in subjects who received post-treatment anticancer therapy than in those who did not. In the lenvatinib arm, median OS was 19.5 months (95% CI: 15.7, 23.0) for subjects who received post-treatment anticancer therapy (43%) and 10.5 months (95% CI: 8.6, 12.2) for those who did not. In the sorafenib arm, median OS was 17.0 months (95% CI: 14.2, 18.8) for subjects who received posttreatment anticancer therapy (51%) and 7.9 months (95% CI: 6.6, 9.7) for those who did not. Median OS was longer by approximately 2.5 months in the lenvatinib compared with the sorafenib arm in both subsets of subjects (with or without post-treatment anticancer therapy).

Endometrial carcinoma

The efficacy of lenvatinib in combination with pembrolizumab was investigated in Study 309, a randomised, multicentre, open-label, active-controlled study conducted in patients with advanced EC who had been previously treated with at least one prior platinum-based chemotherapy regimen in any setting, including in the neoadjuvant and adjuvant settings. Participants may have received up to 2 platinum-containing therapies in total, as long as one was given in the neoadjuvant or adjuvant treatment setting. The study excluded patients with endometrial sarcoma (including carcinosarcoma), or patients who had active autoimmune disease or a medical condition that required immunosuppression. Randomisation was stratified by mismatch repair (MMR) status (dMMR or pMMR [not dMMR]) using a validated IHC test. The pMMR stratum was further stratified by ECOG performance status, geographic region, and history of pelvic radiation. Patients were randomised (1:1) to one of the following treatment arms:

- lenvatinib 20 mg orally once daily in combination with pembrolizumab 200 mg intravenously every 3 weeks.

- investigator’s choice consisting of either doxorubicin 60 mg/m² every 3 weeks, or paclitaxel 80 mg/m² given weekly, 3 weeks on/1 week off.

Treatment with lenvatinib and pembrolizumab continued until RECIST v1.1-defined progression of disease as verified by Blinded Independent Central Review (BICR), unacceptable toxicity, or for pembrolizumab, a maximum of 24 months. Administration of study treatment was permitted beyond RECIST-defined disease progression if the treating investigator considered the patient to be deriving clinical benefit and the treatment was tolerated. A total of 121/411 (29%) of the lenvatinib and pembrolizumab-treated patients received continued study therapy beyond RECIST-defined disease progression. The median duration of post-progression therapy was 2.8 months. Assessment of tumour status was performed every 8 weeks.

A total of 827 patients were enrolled and randomised to lenvatinib in combination with pembrolizumab (n=411) or investigator’s choice of doxorubicin (n=306) or paclitaxel (n=110). The baseline characteristics of these patients were: median age of 65 years (range 30 to 86), 50% age 65 or older; 61% White, 21% Asian, and 4% Black; ECOG PS of 0 (59%) or 1 (41%), and 84% with pMMR tumour status, and 16% with dMMR tumour status. The histologic subtypes were endometrioid carcinoma (60%), serous (26%), clear cell carcinoma (6%), mixed (5%), and other (3%). All 827 of these patients received prior systemic therapy for EC: 69% had one, 28% had two, and 3% had three or more prior systemic therapies. Thirty-seven percent of patients received only prior neoadjuvant or adjuvant therapy. The median duration of study treatment was 7.6 months (range 1 day to 26.8 months). The median duration of exposure to lenvatinib was 6.9 months (range 1 day to 26.8 months).

The primary efficacy outcome measures were OS and PFS (as assessed by BICR using RECIST 1.1). Secondary efficacy outcome measures included ORR, as assessed by BICR using RECIST 1.1. At the pre-specified interim analysis, with a median follow-up time of 11.4 months (range: 0.3 to 26.9 months), the study demonstrated a statistically significant improvement in OS and PFS in the all-comer population.

Efficacy results by MMR subgroups were consistent with overall study results.

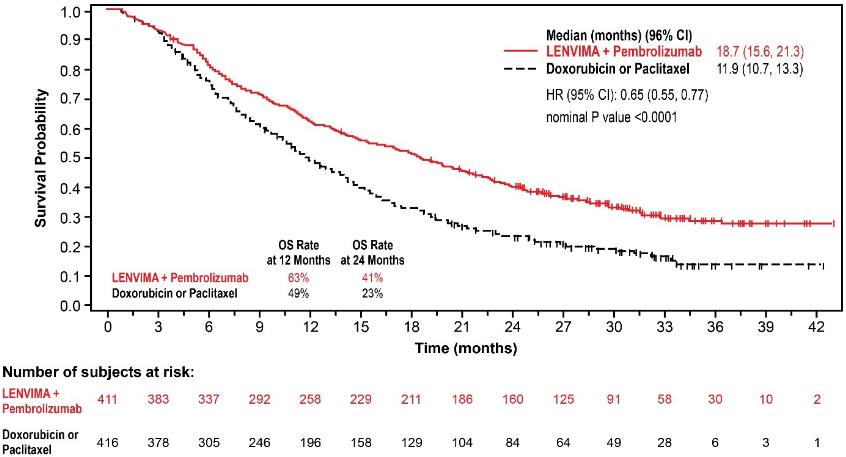

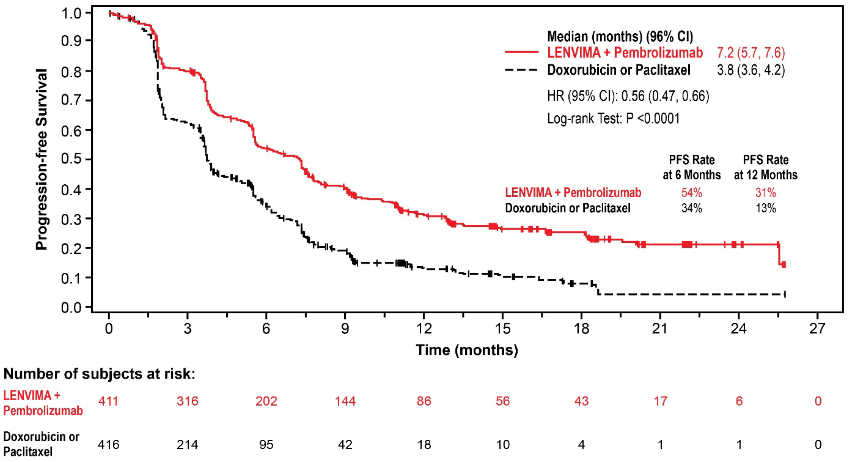

The pre-specified final OS analysis with approximately 16 months of additional follow-up duration from the interim analysis (overall median follow-up time of 14.7 months [range: 0.3 to 43.0 months]) was performed without multiplicity adjustment. The efficacy results in the all-comer population are summarised in Table 9. Kaplan-Meier curves for final OS and interim PFS analyses are shown in Figures 3 and 4, respectively.

Table 9. Efficacy Results in Endometrial Carcinoma in Study 309:

| Endpoint | LENVIMA with pembrolizumab N=411 | Doxorubicin or Paclitaxel N=416 |

|---|---|---|

| OS | ||

| Number (%) of patients with event | 276 (67%) | 329 (79%) |

| Median in months (95% CI) | 18.7 (15.6, 21.3) | 11.9 (10.7, 13.3) |

| Hazard ratioa (95% CI) | 0.65 (0.55, 0.77) | |

| P valueb | <0.0001 | |

| PFSd | ||

| Number (%) of patients with event | 281 (68%) | 286 (69%) |

| Median in months (95% CI) | 7.2 (5.7, 7.6) | 3.8 (3.6, 4.2) |

| Hazard ratioa (95% CI) | 0.56 (0.47, 0.6) | |

| P valuec | <0.0001 | |

| ORRd | ||

| ORRe (95% CI) | 32% (27, 37) | 15% (11,18) |

| Complete response | 7% | 3% |

| Partial response | 25% | 12% |

| P valuef | <0.0001 | |

| Duration of Responsed | ||

| Median in monthsg (range) | 14.4 (1.6+, 23.7+) | 5.7 (0.0+, 24.2+) |

a Based on the stratified Cox regression model.

b One-sided nominal p-Value based on stratified log-rank test (final analysis). At the pre-specified interim analysis of OS with a median follow-up time of 11.4 months (range:0.3 to 26.9 months), statistically significant superiority was achieved for OS comparing the combination of lenvatinib and pembrolizumab with doxorubicin or paclitaxel (HR: 0.62 [95%CI: 0.51, 0.75] p-Value <0.0001).

c One-sided p-Value based on stratified log-rank test.

d At pre-specified interim analysis.

e Response: Best objective response as confirmed complete response or partial response.

f Based on Miettinen and Nurminen method stratified by ECOG performance status, geographic region, and history of pelvic radiation.

g Based on Kaplan-Meier estimation.

Figure 3. Kaplan-Meier Curves for Overall Survival in Study 309*:

* Based on the protocol-specified final analysis

Figure 4. Kaplan-Meier Curves for Progression-Free Survival in Study 309:

QT interval prolongation

A single 32-mg dose of lenvatinib did not prolong the QT/QTc interval based on results from a thorough QT study in healthy volunteers; however, QT/QTc interval prolongation has been reported at a higher incidence in patients treated with lenvatinib than in patients treated with placebo (see sections 4.4 and 4.8).

Paediatric population

The European Medicines Agency has deferred the obligation to submit the results of studies with lenvatinib in one or more subsets of the paediatric population in the treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) and endometrial carcinoma (EC) (see section 4.2 for information on paediatric use).

Paediatric studies

The efficacy of lenvatinib was assessed but not established in four open-label studies: Study 207 was a Phase 1/2, open-label, multi-centre, dose-finding and activity-estimating study of lenvatinib as a single agent and in combination with ifosfamide and etoposide in paediatric patients (aged 2 to <18 years; 2 to ≤25 years for osteosarcoma), with relapsed or refractory solid tumours. A total of 97 patients were enrolled. In the lenvatinib single agent dose-finding cohort, 23 patients were enrolled and received lenvatinib orally, once daily, across 3 dose levels (11, 14, or 17 mg/m²). In the lenvatinib in combination with ifosfamide and etoposide dose-finding cohort, a total of 22 patients were enrolled and received lenvatinib across 2 dose levels (11 or 14 mg/m²). The recommended dose (RD) of lenvatinib as a single agent, and in combination with ifosfamide and etoposide was determined as 14 mg/m² orally, once daily.

In the lenvatinib single agent expansion cohort of relapsed or refractory DTC, the primary efficacy outcome measure was objective response rate (ORR; complete response [CR] + partial response [PR]). One patient was enrolled, and this patient achieved a PR. In both the lenvatinib single agent, and combination with ifosfamide and etoposide expansion cohorts of relapsed or refractory osteosarcoma, the primary efficacy outcome measure was progression-free survival rate at 4 months (PFS-4); the PFS-4 by binomial estimate including all 31 patients treated with lenvatinib as a single agent was 29% (95%CI: 14.2, 48.0); the PFS-4 by binomial estimate in all 20 patients treated in the lenvatinib in combination with ifosfamide and etoposide expansion cohort was 50% (95%CI: 27.2, 72.8).

Study 216 was a multicentre, open-label, single-arm, Phase ½ study to determine the safety, tolerability, and antitumour activity of lenvatinib administered in combination with everolimus in paediatric patients (and young adults aged ≤21 years) with relapsed or refractory solid malignancies, including CNS tumours. A total of 64 patients were enrolled and treated. In Phase 1 (combination dose-finding), 23 patients were enrolled and treated: 5 at Dose Level –1 (lenvatinib 8 mg/m² and everolimus 3 mg/m²) and 18 at Dose Level 1 (lenvatinib 11 mg/m² and everolimus 3 mg/m²). The recommended dose (RD) of the combination was lenvatinib 11 mg/m² and everolimus 3 mg/m², taken once daily. In Phase 2 (combination expansion), 41 patients were enrolled and treated at the RD in the following cohorts: Ewing Sarcoma (EWS, n=10), Rhabdomyosarcoma (RMS, n=20), and High-grade glioma (HGG, n=11). The primary efficacy outcome measure was objective response rate (ORR) at Week 16 in evaluable patients based on investigator assessment using RECIST v1.1 or RANO (for patients with HGG). There were no objective responses observed in the EWS and HGG cohorts; 2 partial responses (PRs) were observed in the RMS cohort for an ORR at Week 16 of 10% (95% CI: 1.2, 31.7).

The OLIE study (Study 230) was a Phase 2, open-label, multi-centre, randomized, controlled trial in patients (aged 2 to ≤25 years) with relapsed or refractory osteosarcoma. A total of 81 patients were randomized in a 1:1 ratio (78 treated; 39 in each arm) to lenvatinib 14 mg/m² in combination with ifosfamide 3000 mg/m² and etoposide 100 mg/m² (Arm A) or ifosfamide 3000 mg/m² and etoposide 100 mg/m² (Arm B). Ifosfamide and etoposide were administered intravenously on Days 1 to 3 of each 21-day cycle for a maximum of 5 cycles. Treatment with lenvatinib was permitted until RECIST v1.1-defined disease progression as verified by Blinded Independent Central Review (BICR) or unacceptable toxicity. The primary efficacy outcome measure was progression-free survival (PFS) per RECIST 1.1 by BICR. The trial did not demonstrate a statistically significant difference in median PFS: 6.5 months (95%CI: 5.7, 8.2) for lenvatinib in combination with ifosfamide and etoposide versus 5.5 months (95%CI: 2.9, 6.5) for ifosfamide and etoposide (HR=0.54 [95%CI: 0.27, 1.08]).

Study 231 is a multicentre, open-label, Phase 2 basket study to evaluate the antitumour activity and safety of lenvatinib in children, adolescents, and young adults between 2 to ≤21 years of age with relapsed or refractory solid malignancies, including EWS, RMS, and HGG. A total of 127 patients were enrolled and treated at the lenvatinib RD (14 mg/m²) in the following cohorts: EWS (n=9), RMS (n=17), HGG (n=8), and other solid tumours (n=9 each for diffuse midline glioma, medulloblastoma, and ependymoma; all other solid tumours n=66). The primary efficacy outcome measure was ORR at Week 16 in evaluable patients based on investigator assessment using RECIST v1.1 or RANO (for patients with HGG). There were no objective responses observed in patients with HGG, diffuse midline glioma, medulloblastoma, or ependymoma. Two PRs were observed in both the EWS and RMS cohorts for an ORR at Week 16 of 22.2% (95% CI: 2.8, 60.0) and 11.8% (95% CI: 1.5, 36.4), respectively. Five PRs (in patients with synovial sarcoma [n=2], kaposiform hemangioendothelioma [n=1], Wilms tumour nephroblastoma [n=1], and clear cell carcinoma [n=1]) were observed among all other solid tumours for an ORR at Week 16 of 7.7% (95% CI: 2.5, 17.0).

Pharmacokinetic properties

Pharmacokinetic parameters of lenvatinib have been studied in healthy adult subjects, adult subjects with hepatic impairment, renal impairment, and solid tumours.

Absorption

Lenvatinib is rapidly absorbed after oral administration with tmax typically observed from 1 to 4 hours postdose. Food does not affect the extent of absorption, but slows the rate of absorption. When administered with food to healthy subjects, peak plasma concentrations are delayed by 2 hours. Absolute bioavailability has not been determined in humans; however, data from a mass-balance study suggest that it is in the order of 85%. Lenvatinib exhibited good oral bioavailability in dogs (70.4%) and monkeys (78.4%).

Distribution

In vitro binding of lenvatinib to human plasma proteins is high and ranged from 98% to 99% (0.3 30 μg/mL, mesilate). This binding was mainly to albumin with minor binding to α1-acid glycoprotein and γ-globulin.

In vitro, the lenvatinib blood-to-plasma concentration ratio ranged from 0.589 to 0.608 (0.1-10 μg/mL, mesilate).

Lenvatinib is a substrate for P-gp and BCRP. Lenvatinib is not a substrate for OAT1, OAT3, OATP1B1, OATP1B3, OCT1, OCT2, MATE1, MATE2-K or the bile salt export pump BSEP.

In patients, the median apparent volume of distribution (Vz/F) of the first dose ranged from 50.5 L to 92 L and was generally consistent across the dose groups from 3.2 mg to 32 mg. The analogous median apparent volume of distribution at steady-state (Vz/Fss) was also generally consistent and ranged from 43.2 L to 121 L.

Biotransformation

In vitro, cytochrome P450 3A4 was demonstrated as the predominant (>80%) isoform involved in the P450-mediated metabolism of lenvatinib. However, in vivo data indicated that non-P450-mediated pathways contributed to a significant portion of the overall metabolism of lenvatinib. Consequently, in vivo, inducers and inhibitors of CYP 3A4 had a minimal effect on lenvatinib exposure (see section 4.5).

In human liver microsomes, the demethylated form of lenvatinib (M2) was identified as the main metabolite. M2' and M3', the major metabolites in human faeces, were formed from M2 and lenvatinib, respectively, by aldehyde oxidase.

In plasma samples collected up to 24 hours after administration, lenvatinib constituted 97% of the radioactivity in plasma radiochromatograms while the M2 metabolite accounted for an additional 2.5%. Based on AUC(0–inf), lenvatinib accounted for 60% and 64% of the total radioactivity in plasma and blood, respectively.

Data from a human mass balance/excretion study indicate lenvatinib is extensively metabolised in humans. The main metabolic pathways in humans were identified as oxidation by aldehyde oxidase, demethylation via CYP3A4, glutathione conjugation with elimination of the O-aryl group (chlorophenyl moiety), and combinations of these pathways followed by further biotransformations (e.g., glucuronidation, hydrolysis of the glutathione moiety, degradation of the cysteine moiety, and intramolecular rearrangement of the cysteinylglycine and cysteine conjugates with subsequent dimerisation). These in vivo metabolic routes align with the data provided in the in vitro studies using human biomaterials.

In vitro transporter studies

For the following transporters, OAT1, OAT3, OATP1B1, OCT1, OCT2, and BSEP, clinically relevant inhibition was excluded based on a cutoff of IC50 >50 × Cmax,unbound.

Lenvatinib showed minimal or no inhibitory activities toward P-gp-mediated and breast cancer resistance protein (BCRP)-mediated transport activities. Similarly, no induction of P-gp mRNA expression was observed.

Lenvatinib showed minimal or no inhibitory effect on OATP1B3 and MATE2-K. Lenvatinib weakly inhibits MATE1. In human liver cytosol, lenvatinib did not inhibit aldehyde oxidase activity.

Elimination

Plasma concentrations decline bi-exponentially following Cmax. The mean terminal exponential half-life of lenvatinib is approximately 28 hours.

Following administration of radiolabelled lenvatinib to 6 patients with solid tumours, approximately two-thirds and one-quarter of the radiolabel were eliminated in the faeces and urine, respectively. The M3 metabolite was the predominant analyte in excreta (~17% of the dose), followed by M2' (~11% of the dose) and M2 (~4.4 of the dose).

Linearity/non-linearity

Dose proportionality and accumulation

In patients with solid tumours administered single and multiple doses of lenvatinib once daily, exposure to lenvatinib (Cmax and AUC) increased in direct proportion to the administered dose over the range of 3.2 to 32 mg once-daily. Lenvatinib displays minimimal accumulation at steady state. Over this range, the median accumulation index (Rac) ranged from 0.96 (20 mg) to 1.54 (6.4 mg). The Rac in HCC subjects with mild and moderate liver impairment was similar to that reported for other solid tumours.

Special populations

Hepatic impairment

The pharmacokinetics of lenvatinib following a single 10-mg dose were evaluated in 6 subjects each with mild and moderate hepatic impairment (Child-Pugh A and Child-Pugh B, respectively). A 5-mg dose was evaluated in 6 subjects with severe hepatic impairment (Child-Pugh C). Eight healthy, demographically matched subjects served as controls and received a 10-mg dose. Lenvatinib exposure, based on dose-adjusted AUC0-t and AUC0-inf data, was 119%, 107%, and 180% of normal for subjects with mild, moderate, and severe hepatic impairment, respectively. It has been determined that plasma protein binding in plasma from hepatically impaired subjects was similar to the respective matched healthy subjects and no concentration dependency was observed. See section 4.2 for dosing recommendation.

There are not sufficient data for HCC patients with Child-Pugh B (moderate hepatic impairment, 3 patients treated with lenvatinib in the pivotal trial) and no data available in Child-Pugh C HCC patients (severe hepatic impairment). Lenvatinib is mainly eliminated via the liver and exposure might be increased in these patient populations.

The median half-life was comparable in subjects with mild, moderate, and severe hepatic impairment as well as those with normal hepatic function and ranged from 26 hours to 31 hours. The percentage of the dose of lenvatinib excreted in urine was low in all cohorts (<2.16% across treatment cohorts).

Renal impairment

The pharmacokinetics of lenvatinib following a single 24-mg dose were evaluated in 6 subjects each with mild, moderate, and severe renal impairment, and compared with 8 healthy, demographically matched subjects. Subjects with end-stage renal disease were not studied.

Lenvatinib exposure, based on AUC0-inf data, was 101%, 90%, and 122% of normal for subjects with mild, moderate, and severe renal impairment, respectively. It has been determined that plasma protein binding in plasma from renally impaired subjects was similar to the respective matched healthy subjects and no concentration dependency was observed. See section 4.2 for dosing recommendation.

Age, sex, weight, race

Based on a population pharmacokinetic analysis of patients receiving up to 24 mg lenvatinib once daily, age, sex, weight, and race (Japanese vs. other, Caucasian vs. other) had no clinically relevant effects on clearance (see section 4.2).

Paediatric Population

Based on a population pharmacokinetics analysis in paediatric patients of 2 to 12 years old, which included data from 3 paediatric patients aged 2 to <3 years, 28 paediatric patients aged ≥3 to <6 years and 89 paediatric patients aged 6 to ≤12 years across the lenvatinib paediatric program, lenvatinib oral clearance (CL/F) was affected by body weight but not age. Predicted exposure levels in terms of area under the curve at steady-state (AUCss) in paediatric patients receiving 14 mg/m 2 were comparable to those in adult patients receiving a fixed dose of 24 mg. In these studies, there were no apparent differences in the pharmacokinetics of active substance lenvatinib among children (2–12 years), adolescents, and young adult patients with studied tumour types, but data in children are relatively limited to draw definite conclusions (see section 4.2).

Preclinical safety data

In the repeated-dose toxicity studies (up to 39 weeks), lenvatinib caused toxicologic changes in various organs and tissues related to the expected pharmacologic effects of lenvatinib including glomerulopathy, testicular hypocellularity, ovarian follicular atresia, gastrointestinal changes, bone changes, changes to the adrenals (rats and dogs), and arterial (arterial fibrinoid necrosis, medial degeneration, or haemorrhage) lesions in rats, dogs, and cynomolgus monkeys. Elevated transaminase levels asociated with signs of hepatotoxicity, were also observed in rats, dogs and monkeys. Reversibility of the toxicologic changes was observed at the end of a 4-week recovery period in all animal species investigated.

Genotoxicity

Lenvatinib was not genotoxic.

Carcinogenicity studies have not been conducted with lenvatinib.

Reproductive and developmental toxicity

No specific studies with lenvatinib have been conducted in animals to evaluate the effect on fertility. However, testicular (hypocellularity of the seminiferous epithelium) and ovarian changes (follicular atresia) were observed in repeated-dose toxicity studies in animals at exposures 11 to 15 times (rat) or 0.6 to 7 times (monkey) the anticipated clinical exposure (based on AUC) at the maximum tolerated human dose. These findings were reversible at the end of a 4-week recovery period.

Administration of lenvatinib during organogenesis resulted in embryolethality and teratogenicity in rats (foetal external and skeletal anomalies) at exposures below the clinical exposure (based on AUC) at the maximum tolerated human dose, and rabbits (foetal external, visceral or skeletal anomalies) based on body surface area; mg/m² at the maximum tolerated human dose. These findings indicate that lenvatinib has a teratogenic potential, likely related to the pharmacologic activity of lenvatinib as an antiangiogenic agent.

Lenvatinib and its metabolites are excreted in rat milk.

Juvenile animal toxicity studies

Mortality was the dose-limiting toxicity in juvenile rats in which dosing was initiated on postnatal day (PND) 7 or PND21 and was observed at exposures that were respectively 125- or 12-fold lower compared with the exposure at which mortality was observed in adult rats, suggesting an increasing sensitivity to toxicity with decreasing age. Therefore, mortality may be attributed to complications related to primary duodenal lesions with possible contribution from additional toxicities in immature target organs.

The toxicity of lenvatinib was more prominent in younger rats (dosing initiated on PND7) compared with those with dosing initiated on PND21 and mortality and some toxicities were observed earlier in the juvenile rats at 10 mg/kg compared with adult rats administered the same dose level. Growth retardation, secondary delay of physical development, and lesions attributable to pharmacologic effects (incisors, femur [epiphyseal growth plate], kidneys, adrenals, and duodenum) were also observed in juvenile rats.

© All content on this website, including data entry, data processing, decision support tools, "RxReasoner" logo and graphics, is the intellectual property of RxReasoner and is protected by copyright laws. Unauthorized reproduction or distribution of any part of this content without explicit written permission from RxReasoner is strictly prohibited. Any third-party content used on this site is acknowledged and utilized under fair use principles.