OTEZLA Film-coated tablet Ref.[6207] Active ingredients: Apremilast

Source: European Medicines Agency (EU) Revision Year: 2024 Publisher: Amgen Europe B.V., Minervum 7061, 4817 ZK Breda, The Netherlands

Pharmacodynamic properties

Pharmacotherapeutic group: Immunosupressants, selective immunosuppressants

ATC code: L04AA32

Mechanism of action

Apremilast, an oral small-molecule inhibitor of phosphodiesterase 4 (PDE4), works intracellularly to modulate a network of pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory mediators. PDE4 is a cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP)-specific PDE and the dominant PDE in inflammatory cells. PDE4 inhibition elevates intracellular cAMP levels, which in turn down-regulates the inflammatory response by modulating the expression of TNF-α, IL-23, IL-17 and other inflammatory cytokines. Cyclic AMP also modulates levels of anti-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-10. These pro- and anti-inflammatory mediators have been implicated in psoriatic arthritis and psoriasis.

Pharmacodynamic effects

In clinical studies in patients with psoriatic arthritis, apremilast significantly modulated, but did not fully inhibit, plasma protein levels of IL-1α, IL-6, IL-8, MCP-1, MIP-1β, MMP-3, and TNF-α. After 40 weeks of treatment with apremilast, there was a decrease in plasma protein levels of IL-17 and IL-23, and an increase in IL-10. In clinical studies in patients with psoriasis, apremilast decreased lesional skin epidermal thickness, inflammatory cell infiltration, and expression of pro-inflammatory genes, including those for inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS), IL-12/IL-23p40, IL-17A, IL-22 and IL-8. In clinical studies in patients with Behçet Disease treated with apremilast, there was a significant positive association between the change in plasma TNF-alpha and clinical efficacy as measured by the number of oral ulcers.

Apremilast administered at doses of up to 50 mg twice daily did not prolong the QT interval in healthy subjects.

Clinical efficacy and safety

Psoriatic Arthritis

The safety and efficacy of apremilast were evaluated in 3 multi-centre, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled studies (Studies PALACE 1, PALACE 2, and PALACE 3) of similar design in adult patients with active PsA (≥3 swollen joints and ≥3 tender joints) despite prior treatment with small molecule or biologic DMARDs. A total of 1 493 patients were randomised and treated with either placebo, apremilast 20 mg or apremilast 30 mg given orally twice daily.

Patients in these studies had a diagnosis of PsA for at least 6 months. One qualifying psoriatic skin lesion (at least 2 cm in diameter) was also required in PALACE 3. Apremilast was used as a monotherapy (34.8%) or in combination with stable doses of small molecule DMARDs (65.2%). Patients received apremilast in combination with one or more of the following: methotrexate (MTX, ≤25 mg/week, 54.5%), sulfasalazine (SSZ, ≤2 g/day, 9.0%), and leflunomide (LEF; ≤20 mg/day, 7.4%). Concomitant treatment with biologic DMARDs, including TNF blockers, was not allowed. Patients with each subtype of PsA were enrolled in the 3 studies, including symmetric polyarthritis (62.0%), asymmetric oligoarthritis (26.9%), distal interphalangeal (DIP) joint arthritis (6.2%), arthritis mutilans (2.7%), and predominant spondylitis (2.1%). Patients with pre-existing enthesopathy (63%) or pre-existing dactylitis (42%) were enrolled. A total of 76.4% of patients were previously treated with only small-molecule DMARDs and 22.4% of patients were previously treated with biologic DMARDs, which includes 7.8% who had a therapeutic failure with a prior biologic DMARD. The median duration of PsA disease was 5 years.

Based on the study design, patients whose tender and swollen joint counts had not improved by at least 20% were considered non-responders at week 16. Placebo patients who were considered non-responders were re-randomised 1:1 in a blinded fashion to either apremilast 20 mg twice daily or 30 mg twice daily. At week 24, all remaining placebo-treated patients were switched to either apremilast 20 or 30 mg twice daily. Following 52 weeks of treatment, patients could continue on open label apremilast 20 mg or 30 mg within the long-term extension of the PALACE 1, PALACE 2, and PALACE 3 studies for a total duration of treatment up to 5 years (260 weeks).

The primary endpoint was the percentage of patients achieving American College of Rheumatology (ACR) 20 response at week 16.

Treatment with apremilast resulted in significant improvements in the signs and symptoms of PsA, as assessed by the ACR 20 response criteria compared to placebo at weeks 16. The proportion of patients with ACR 20/50/70 (responses in studies PALACE 1, PALACE 2 and PALACE 3, and the pooled data for studies PALACE 1, PALACE 2 and PALACE 3) for apremilast 30 mg twice daily at week 16 are shown in table 4. ACR 20/50/70 responses were maintained at week 24

Among patients who were initially randomised to apremilast 30 mg twice daily treatment, ACR 20/50/70 response rates were maintained through week 52 in the pooled studies PALACE 1, PALACE 2 and PALACE 3 (figure 1).

Table 4. Proportion of patients with ACR responses in studies PALACE 1, PALACE 2 and PALACE 3 and pooled studies at week 16:

| PALACE 1 | PALACE 2 | PALACE 3 | POOLED | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Na | Placebo +/- DMARDs N=168 | Apremilast 30 mg twice daily +/- DMARDs N=168 | Placebo +/- DMARDs N=159 | Apremilast 30 mg twice daily +/- DMARDs N=162 | Placebo +/- DMARDs N=169 | Apremilast 30 mg twice daily +/- DMARDs N=167 | Placebo +/- DMARDs N=496 | Apremilast 30 mg twice daily +/- DMARDs N=497 |

| ACR 20a | ||||||||

| Week 16 | 19.0% | 38.1%** | 18.9% | 32.1%* | 18.3% | 40.7%** | 18.8% | 37.0%** |

| ACR 50 | ||||||||

| Week 16 | 6.0% | 16.1%* | 5.0% | 10.5% | 8.3% | 15.0% | 6.5% | 13.9%** |

| ACR 70 | ||||||||

| Week 16 | 1.2% | 4.2% | 0.6% | 1.2% | 2.4% | 3.6% | 1.4% | 3.0% |

* p≤0.01 for apremilast vs. placebo

** p≤0.001 for apremilast vs. placebo

a N is the number of patients as randomised and treated

Figure 1. Proportion of ACR 20/50/70 responders through week 52 in the pooled analysis of studies PALACE 1, PALACE 2 and PALACE 3 (NRI*):

* NRI: None responder imputation. Subjects who discontinued early prior to the time point and subjects who did not have sufficient data for a definitive determination of response status at the time point are counted as non-responders.

Among 497 patients initially randomised to apremilast 30 mg twice daily, 375 (75%) patients were still on this treatment on week 52. In these patients, ACR 20/50/70 responses at week 52 were of 57%, 25%, and 11% respectively. Among 497 patients initially randomised to apremilast 30 mg twice daily, 375 (75%) patients entered the long term extension studies, and of these, 221 patients (59%) were still on this treatment at week 260. ACR responses were maintained in the long-term open label extension studies for up to 5 years.

Responses observed in the apremilast treated group were similar in patients receiving and not receiving concomitant DMARDs, including MTX. Patients previously treated with DMARDs or biologics who received apremilast achieved a greater ACR 20 response at week 16 than patients receiving placebo.

Similar ACR responses were observed in patients with different PsA subtypes, including DIP. The number of patients with arthritis mutilans and predominant spondylitis subtypes was too small to allow meaningful assessment.

In PALACE 1, PALACE 2 and PALACE 3, improvements in Disease Activity Scale (DAS) 28 C-reactive protein (CRP) and in the proportion of patients achieving a modified PsA response criteria (PsARC) were greater in the apremilast group, compared to placebo at week 16 (nominal p-value p<0.0004, p-value≤0.0017, respectively). These improvements were maintained at week 24. Among patients who remained on the apremilast treatment to which they were randomised at study start, DAS28 (CRP) score and PsARC response were maintained through week 52.

At weeks 16 and 24 improvements in parameters of peripheral activity characteristic of psoriatic arthritis (e.g. number of swollen joints, number of painful/tender joints, dactylitis and enthesitis) and in the skin manifestations of psoriasis were seen in the apremilast-treated patients. Among patients who remained on the apremilast treatment to which they were randomised at study start, these improvements were maintained through week 52.

The clinical responses were maintained in the same parameters of peripheral activity and in the skin manifestations of psoriasis in the open-label extension studies for up to 5 years of treatment.

Physical function and health-related quality of life

Apremilast-treated patients demonstrated statistically significant improvement in physical function, as assessed by the disability index of the health assessment questionnaire (HAQ-DI) change from baseline, compared to placebo at weeks 16 in PALACE 1, PALACE 2 and PALACE 3 and in the pooled studies. Improvement in HAQ-DI scores was maintained at week 24.

Among patients who were initially randomised to apremilast 30 mg twice daily treatment, the change from baseline in the HAQ-DI score at week 52 was -0.333 in the apremilast 30 mg twice daily group in a pooled analysis of the open label phase of studies PALACE 1, PALACE 2 and PALACE 3.

In studies PALACE 1, PALACE 2 and PALACE 3, significant improvements were demonstrated in health-related quality of life, as measured by the changes from baseline in the physical functioning (PF) domain of the Short Form Health Survey version 2 (SF-36v2), and in the Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy – Fatigue (FACIT-fatigue) scores in patients treated with apremilast compared to placebo at weeks 16 and 24. Among patients who remained on the apremilast treatment, to which they were initially randomised at study start, improvement in physical function and FACIT-fatigue was maintained through week 52.

Improved physical function as assessed by the HAQ-DI and the SF36v2PF domain, and the FACIT-fatigue scores were maintained in the open-label extension studies for up to 5 years of treatment.

Adult psoriasis

The safety and efficacy of apremilast were evaluated in two multicentre, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled studies (Studies ESTEEM 1 and ESTEEM 2) which enrolled a total of 1 257 patients with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis who had a body surface area (BSA) involvement of ≥10%, Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI) score ≥12, static Physician Global Assessment (sPGA) of ≥3 (moderate or severe), and who were candidates for phototherapy or systemic therapy.

These studies had a similar design through week 32. In both studies, patients were randomised 2:1 to apremilast 30 mg twice daily or placebo for 16 weeks (placebo-controlled phase) and from weeks 16-32, all patients received apremilast 30 mg twice daily (maintenance phase). During the Randomised Treatment Withdrawal Phase (weeks 32-52), patients originally randomised to apremilast who achieved at least a 75% reduction in their PASI score (PASI-75) (ESTEEM 1) or a 50% reduction in their PASI score (PASI-50) (ESTEEM 2) were re-randomised at week 32 to either placebo or apremilast 30 mg twice daily. Patients who were re-randomised to placebo and who lost PASI-75 response (ESTEEM 1) or lost 50% of the PASI improvement at week 32 compared to baseline (ESTEEM 2) were retreated with apremilast 30 mg twice daily. Patients who did not achieve the designated PASI response by week 32, or who were initially randomised to placebo, remained on apremilast until week 52. The use of low potency topical corticosteroids on the face, axillae, and groin, coal tar shampoo and/or salicylic acid scalp preparations was permitted throughout the studies. In addition, at week 32, subjects who did not achieve a PASI-75 response in ESTEEM 1, or a PASI-50 response in ESTEEM 2, were permitted to use topical psoriasis therapies and/or phototherapy in addition to apremilast 30 mg twice daily treatment.

Following 52 weeks of treatment, patients could continue on open-label apremilast 30 mg within the long-term extension of the ESTEEM 1 and ESTEEM 2 studies for a total duration of treatment up to 5 years (260 weeks).

In both studies, the primary endpoint was the proportion of patients who achieved PASI-75 at week 16. The major secondary endpoint was the proportion of patients who achieved a sPGA score of clear (0) or almost clear (1) at week 16.

The mean baseline PASI score was 19.07 (median 16.80), and the proportion of patients with sPGA score of 3 (moderate) and 4 (severe) at baseline was 70.0% and 29.8%, respectively with a mean baseline BSA involvement of 25.19% (median 21.0%). Approximately 30% of all patients had received prior phototherapy and 54% had received prior conventional systemic and/or biologic therapy for the treatment of psoriasis (including treatment failures), with 37% receiving prior conventional systemic therapy and 30% receiving prior biologic therapy. Approximately one-third of patients had not received prior phototherapy, conventional systemic or biologic therapy. A total of 18% of patients had a history of psoriatic arthritis.

The proportion of patients achieving PASI-50, -75 and -90 responses, and sPGA score of clear (0) or almost clear (1), are presented in table 5 below. Treatment with apremilast resulted in significant improvement in moderate to severe plaque psoriasis as demonstrated by the proportion of patients with PASI-75 response at week 16, compared to placebo. Clinical improvement measured by sPGA, PASI-50 and PASI-90 responses were also demonstrated at week 16. In addition, apremilast demonstrated a treatment benefit across multiple manifestations of psoriasis including pruritus, nail disease, scalp involvement and quality of life measures.

Table 5. Clinical response at week 16 in studies ESTEEM 1 and ESTEEM 2 (FASa, LOCFb):

| ESTEEM 1 | ESTEEM 2 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Placebo | 30 mg twice daily APR* | Placebo | 30 mg twice daily APR* | |

| N | 282 | 562 | 137 | 274 |

| PASIc 75, n (%) | 15 (5.3) | 186 (33.1) | 8 (5.8) | 79 (28.8) |

| sPGAd of clear or almost clear, n (%) | 11 (3.9) | 122 (21.7) | 6 (4.4) | 56 (20.4) |

| PASI 50, n (%) | 48 (17.0) | 330 (58.7) | 27 (19.7) | 152 (55.5) |

| PASI 90, n (%) | 1 (0.4) | 55 (9.8) | 2 (1.5) | 24 (8.8) |

| Percent change BSAe (%) mean ± SD | -6.9 ± 38.95 | -47.8 ± 38.48 | -6.1 ± 47.57 | -48.4 ± 40.78 |

| Change in pruritus VASf (mm), mean ± SD | -7.3 ± 27.08 | -31.5 ± 32.43 | -12.2 ± 30.94 | -33.5 ± 35.46 |

| Change in DLQIg, mean ± SD | -2.1 ± 5.69 | -6.6 ± 6.66 | -2.8 ± 7.22 | -6.7 ± 6.95 |

| Change in SF-36 MCSh, mean ± SD | -1.02 ± 9.161 | 2.39 ± 9.504 | 0.00 ± 10.498 | 2.58 ± 10.129 |

* p<0.0001 for apremilast vs placebo, except for ESTEEM 2 PASI 90 and Change in SF-36 MCS where p=0.0042 and p=0.0078, respectively.

a FAS = Full Analysis Set

b LOCF = Last Observation Carried Forward

c PASI = Psoriasis Area and Severity Index

d sPGA = Static Physician Global Assessment

e BSA = Body Surface Area

f VAS = Visual Analog Scale; 0 = best, 100 = worst

g DLQI = Dermatology Life Quality Index; 0 = best, 30 = worst

h SF-36 MCS = Medical Outcome Study Short Form 36-Item Health Survey, Mental Component Summary

The clinical benefit of apremilast was demonstrated across multiple subgroups defined by baseline demographics and baseline clinical disease characteristics (including psoriasis disease duration and patients with a history of psoriatic arthritis). The clinical benefit of apremilast was also demonstrated regardless of prior psoriasis medication usage and response to prior psoriasis treatments. Similar response rates were observed across all weight ranges.

Response to apremilast was rapid, with significantly greater improvements in the signs and symptoms of psoriasis, including PASI, skin discomfort/pain and pruritus, compared to placebo by week 2. In general, PASI responses were achieved by week 16 and were maintained through week 32.

In both studies, the mean percent improvement in PASI from baseline remained stable during the randomised treatment withdrawal phase for patients re-randomised to apremilast at week 32 (table 6).

Table 6. Persistence of effect among subjects randomised to APR 30 twice daily at week 0 and re-randomised to APR 30 twice daily at week 32 to week 52:

| Time Point | ESTEEM 1 | ESTEEM 2 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Patients who achieved PASI-75 at week 32 | Patients who achieved PASI-50 at week 32 | ||

| Percent Change in PASI from baseline, mean (%) ± SDa | Week 16 | -77.7 ± 20.30 | -69.7 ± 24.23 |

| Week 32 | -88 ± 8.30 | -76.7 ± 13.42 | |

| Week 52 | -80.5 ± 12.60 | -74.4 ± 18.91 | |

| Change in DLQI from baseline, mean ± SDa | Week 16 | -8.3 ± 6.26 | -7.8 ± 6.41 |

| Week 32 | -8.9 ± 6.68 | -7.7 ± 5.92 | |

| Week 52 | -7.8 ± 5.75 | -7.5 ± 6.27 | |

| Proportion of subjects with Scalp Psoriasis PGA (ScPGA) 0 or 1, n/N (%)b | Week 16 | 40/48 (83.3) | 21/37 (56.8) |

| Week 32 | 39/48 (81.3) | 27/37 (73.0) | |

| Week 52 | 35/48 (72.9) | 20/37 (54.1) |

a Includes subjects re-randomised to APR 30 twice daily at week 32 with a baseline value and a post-baseline value at the evaluated study week.

b N is based on subjects with moderate or greater scalp psoriasis at baseline who were re-randomised to APR 30 twice daily at week 32. Subjects with missing data were counted as nonresponders.

In study ESTEEM 1, approximately 61% of patients re-randomised to apremilast at week 32 had a PASI-75 response at week 52. Of the patients with at least a PASI-75 response who were re-randomised to placebo at week 32 during a randomised treatment withdrawal phase, 11.7% were PASI-75 responders at week 52. The median time to loss of PASI-75 response among the patients re-randomised to placebo was 5.1 weeks.

In study ESTEEM 2, approximately 80.3% of patients re-randomised to apremilast at week 32 had a PASI-50 response at week 52. Of the patients with at least a PASI-50 response who were re-randomised to placebo at week 32, 24.2% were PASI-50 responders at week 52. The median time to loss of 50% of their week 32 PASI improvement was 12.4 weeks.

After randomised withdrawal from therapy at week 32, approximately 70% of patients in study ESTEEM 1, and 65.6% of patients in study ESTEEM 2, regained PASI-75 (ESTEEM 1) or PASI-50 (ESTEEM 2) responses after re-initiation of apremilast treatment. Due to the study design the duration of re-treatment was variable, and ranged from 2.6 to 22.1 weeks.

In study ESTEEM 1, patients randomised to apremilast at the start of the study who did not achieve a PASI-75 response at week 32 were permitted to use concomitant topical therapies and/or UVB phototherapy between weeks 32 to 52. Of these patients, 12% achieved a PASI-75 response at week 52 with apremilast plus topical and/or phototherapy treatment.

In studies ESTEEM 1 and ESTEEM 2, significant improvements (reductions) in nail psoriasis, as measured by the mean percent change in Nail Psoriasis Severity Index (NAPSI) from baseline, were observed in patients receiving apremilast compared to placebo-treated patients at week 16 (p<0.0001 and p=0.0052, respectively). Further improvements in nail psoriasis were observed at week 32 in patients continuously treated with apremilast.

In studies ESTEEM 1 and ESTEEM 2, significant improvements in scalp psoriasis of at least moderate severity (≥3), measured by the proportion of patients achieving Scalp Psoriasis Physician's Global Assessment (ScPGA) of clear (0) or minimal (1) at week 16, were observed in patients receiving apremilast compared to placebo-treated patients (p<0.0001 for both studies). The improvements were generally maintained in subjects who were re-randomised to apremilast at week 32 through week 52 (table 6).

In studies ESTEEM 1 and ESTEEM 2, significant improvements in quality of life as measured by the Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI) and the SF-36v2MCS were demonstrated in patients receiving apremilast compared with placebo-treated patients (table 5). Improvements in DLQI were maintained through week 52 in subjects who were re-randomised to apremilast at week 32 (table 6). In addition, in study ESTEEM 1, significant improvement in the Work Limitations Questionnaire (WLQ- 25) Index was achieved in patients receiving apremilast compared to placebo.

Among 832 patients initially randomised to apremilast 30 mg twice daily, 443 patients (53%) entered the open-label extension studies of ESTEEM 1 and ESTEEM 2, and of these 115 patients (26%) were still on treatment at week 260. For patients who remained on apremilast in the open label extension of ESTEEM 1 and ESTEEM 2 studies, improvements were generally maintained in PASI score, affected BSA, itch, nail and quality of life measures for up to 5 years.

The long-term safety of apremilast 30 mg twice daily in patients with psoriatic arthritis and psoriasis was assessed for a total duration of treatment up to 5 years. Long-term experience in open-label extension studies with apremilast was generally comparable to the 52-week studies.

Paediatric psoriasis

A multicentre, randomised, double blind, placebo- controlled trial (SPROUT) was conducted in 245 paediatric subjects 6 to 17 years of age (inclusive) with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis who were candidates for phototherapy or systemic therapy. Enrolled subjects had an sPGA score of ≥3 (moderate or severe disease), BSA involvement of ≥10%, and PASI score of ≥12, with psoriasis that was inadequately controlled by or inappropriate for topical therapy. Subjects were randomised 2:1 to receive either apremilast (n=163) or placebo (n=82) for 16 weeks.

Subjects with a baseline weight of 20 kg to < 50 kg received apremilast 20 mg twice daily or placebo twice daily, and subjects with a baseline weight ≥ 50 kg received apremilast 30 mg twice daily or placebo twice daily. At week 16, the placebo group was switched to receive apremilast (with dose based on baseline weight) and the apremilast group remained on drug (according to their original dosing assignment) through week 52. Subjects were allowed to use low-potency or weak topical corticosteroids on the face, axilla, and groin and unmedicated skin moisturizers for body lesions only.

The primary endpoint was the proportion of subjects who achieved an sPGA response (defined as a score of clear [0] or almost clear [1] with at least a 2-point reduction from baseline) at week 16. The key secondary endpoint was the proportion of subjects who achieved a PASI-75 response (at least a 75% reduction in PASI score from baseline) at week 16. Other endpoints at week 16 included the proportions of subjects who achieved a PASI-50 response (at least 50% reduction in PASI score from baseline), PASI-90 response (at least 90% reduction in PASI score from baseline), and Children's Dermatology Life Quality Index (CDLQI) response (CDLQI total score of 0 or 1), percent change from baseline in affected BSA, change from baseline in PASI score, and change from baseline in the CDLQI total score.

Enrolled subjects ranged in age from 6 to 17 years, with a median age of 13 years; 41.2% of subjects were 6 to 11 years of age and 58.8% of subjects were 12 to 17 years of age. The mean baseline BSA involvement was 31.5% (median 26.0%), the mean baseline PASI score was 19.8 (median 17.2), and the proportions of subjects with an sPGA score of 3 (moderate) and 4 (severe) at baseline were 75.5% and 24.5%, respectively. Of the enrolled subjects, 82.9% did not receive prior conventional systemic therapy, 82.4% did not receive prior phototherapy and 94.3% were biologic-naïve.

The efficacy results at week 16 are presented in table 7.

Table 7. Efficacy results at week 16 in paediatric subjects with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis (ITT population):

| SPROUT | ||

|---|---|---|

| Endpointa | Placebo | Apremilast |

| Number of subjects randomised | N=82 | N=163 |

| sPGA responseb | 11.5% | 33.1% |

| PASI-75 responseb | 16.1% | 45.4% |

| PASI-50 responseb | 32.1% | 70.5% |

| PASI-90 responseb | 4.9% | 25.2% |

| Percent change from baseline in affected BSAc | -21.82 ± 5.104 | -56.59 ± 3.558 |

| Change from baseline in CDLQI scorec,d | -3.2 ± 0.45 | -5.1 ± 0.31 |

| Number of subjects with baseline CDLQI score ≥2 | N=76 | N=148 |

| CDLQI responseb | 31.3% | 35.4% |

BSA = body surface area; CDLQI = Children's Dermatology Life Quality Index; ITT = intent to treat; PASI = Psoriasis Area and Severity Index; sPGA = Static Physician Global Assessment

a Apremilast 20 or 30 mg twice daily vs. placebo at week 16; p-value<0.0001 for sPGA response and PASI-75 response, nominal p-value<0.01 for all other end points except CDLQI response (nominal p-value 0.5616)

b Proportion of subjects who achieved the response

c Least squares mean +/- standard error

d 0 = best score, 30 = worst score

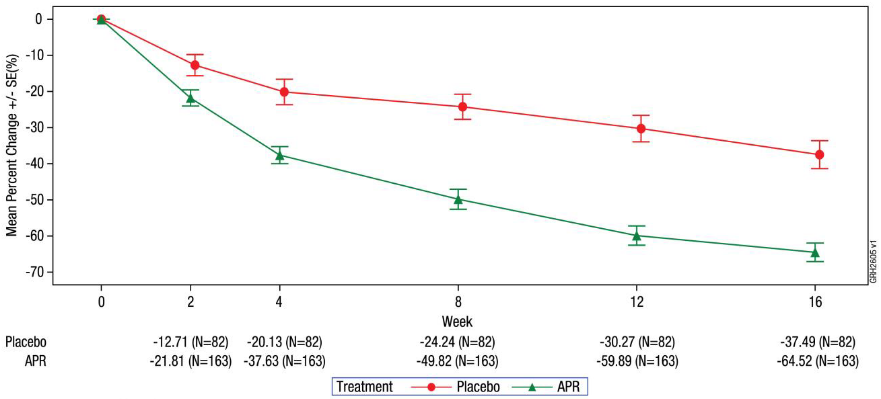

The mean percent change from baseline in total PASI score in apremilast-treated and placebo-treated subjects during the placebo-controlled phase is presented in figure 2.

Figure 2. Percent change from baseline in total PASI score through week 16 (ITT population; MI):

ITT = Intent-To-Treat. MI = Multiple Imputation.

Among patients originally randomised to apremilast, sPGA response, PASI-75 response, and the other endpoints achieved at week 16 were maintained through week 52.

Behçet's disease

The safety and efficacy of apremilast were evaluated in a phase 3, multicentre, randomised, placebo-controlled study (RELIEF) in adult patients with active Behçet's Disease (BD) with oral ulcers. Patients were previously treated with at least one non-biologic BD medication for oral ulcers and were candidates for systemic therapy. Concomitant treatment for BD was not allowed. The population studied met the International Study Group (ISG) criteria for BD with a history of skin lesions (98.6%), genital ulcers (90.3%), musculoskeletal (72.5%), ocular (17.4%), central nervous system (9.7%) or GI manifestations (9.2%), epididymitis (2.4%) and vascular involvement (1.4%). Patients with severe BD, defined as those with active major organ involvement (for ex. meningoencephalitis or pulmonary artery aneurysm) were excluded.

A total of 207 BD patients were randomised 1:1 to receive either apremilast 30 mg twice daily (n=104) or placebo (n=103) for 12-weeks (placebo-controlled phase) and from weeks 12 to 64, all patients received apremilast 30 mg twice daily (active treatment phase). Patients ranged in age from 19 to 72 years, with a mean age of 40 years. The mean duration of BD was 6.84 years. All patients had a history of recurrent oral ulcers with at least 2 oral ulcers at screening and randomisation: the mean baseline oral ulcer counts were 4.2 and 3.9 in the apremilast and placebo groups, respectively.

The primary endpoint was the Area Under the Curve (AUC) for the number of oral ulcers from baseline through week 12. Secondary endpoints included other measures of oral ulcers: oral ulcer pain Visual Analog Scale (VAS), proportion of patients who are oral ulcer-free (complete response), time to onset of oral ulcer resolution, and proportion of patients achieving resolution of oral ulcers by week 6, and who remain oral ulcer free at every visit for at least 6 additional weeks during the 12-week placebo-controlled treatment phase. Other endpoints included Behçet's Syndrome Activity Score (BSAS), BD Current Activity Form (BDCAF), including the BD Current Activity Index (BDCAI) score, the Patient's Perception of Disease Activity, the Clinician's Overall Perception of Disease Activity and the BD Quality of Life Questionnaire (BD QoL).

Measure of oral ulcers

Apremilast 30 mg twice daily resulted in significant improvement in oral ulcers as demonstrated by the AUC for the number of oral ulcers from baseline through week 12 (p<0.0001), compared with placebo.

Significant improvements in other measures of oral ulcers were demonstrated at week 12.

Table 8. Clinical response of oral ulcers at week 12 in RELIEF (ITT population):

| Endpoint^a^ | Placebo N=103 | Apremilast 30 mg BID N=104 |

|---|---|---|

| AUC^b^ for the number of oral ulcers from baseline through week 12 (MI) | LS Mean 222.14 | LS Mean 129.54 |

| Change from baseline in the pain of oral ulcers as measured by VAS^c^ at week 12 (MMRM) | LS Mean -18.7 | LS Mean -42.7 |

| Proportion of subjects achieving resolution of oral ulcers (oral ulcer-free) by week 6, and who remain oral ulcer free at every visit for at least 6 additional weeks during the 12-week placebo- controlled treatment phase | 4.9% | 29.8% |

| Median time (weeks) to oral ulcer resolution during the placebo- controlled treatment phase | 8.1 weeks | 2.1 weeks |

| Proportion of subjects with complete oral ulcer response at week 12 (NRI) | 22.3% | 52.9% |

| Proportion of subjects with partial oral ulcer responsed at week 12 (NRI) | 47.6% | 76.0% |

ITT = intent to treat; LS = least squares; MI = multiple imputation; MMRM = mixed-effects model for repeated measures; NRI = non-responder imputation; BID = twice daily.

a p-value<0.0001 for all apremilast vs. placebo

b AUC = Area Under the Curve.

c VAS = Visual Analog Scale; 0 = no pain, 100 = worst possible pain.

d Partial oral ulcer response = number of oral ulcers reduced by ≥50% post baseline (Exploratory analysis); nominal p-value – <0.0001

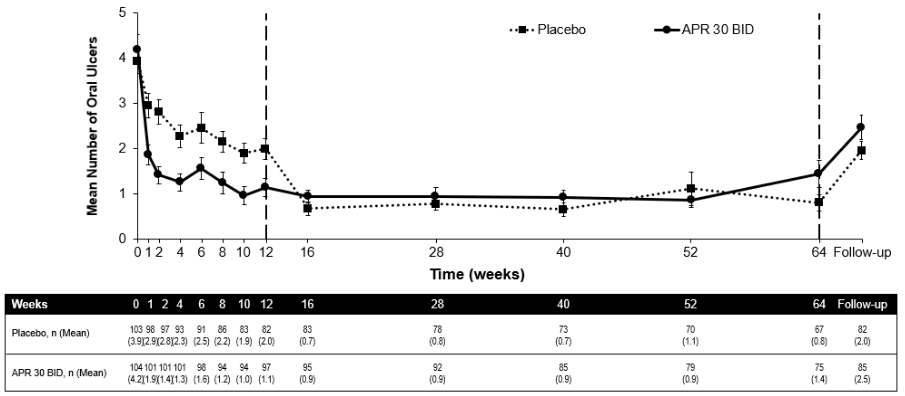

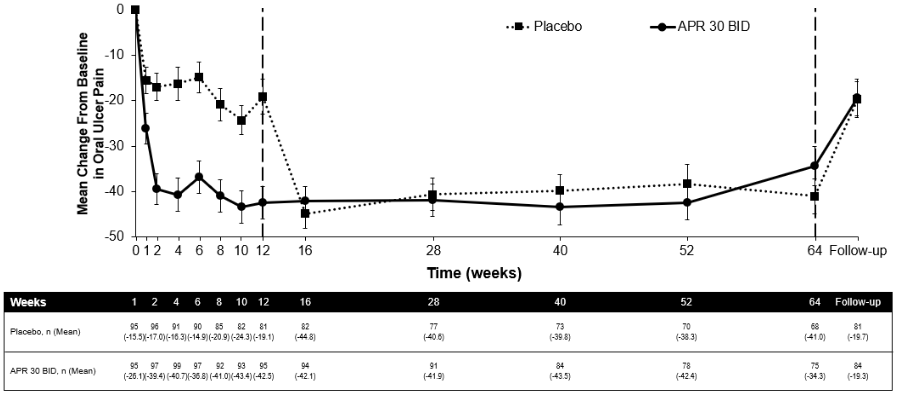

Among 104 patients originally randomised to apremilast 30 mg twice daily, 75 patients (approximately 72%) remained on this treatment at week 64. A significant reduction in the mean number of oral ulcers and oral ulcer pain was observed in the apremilast 30 mg twice daily treatment group compared to the placebo treatment group at every visit, as early as week 1, through week 12 for number of oral ulcers (p≤0.0015) and for oral ulcer pain (p≤0.0035). Among patients who were continuously treated with apremilast and remained in the study, improvements in oral ulcers and reduction of oral ulcer pain were maintained through week 64 (figures 3 and 4).

Among patients originally randomised to apremilast 30 mg twice daily who remained in the study, the proportions of patients with a complete response and partial response of oral ulcers were maintained through week 64 (53.3% and 76.0% respectively).

Figure 3. Mean number of oral ulcers by time point through week 64 (ITT population; DAO):

TT = Intent To Treat; DAO = Data As Observed.

APR 30 BID = apremilast 30 mg twice daily.

Note: Placebo or APR 30 mg BID indicates the treatment group in which patients were randomised. Placebo treatment group patients switched to APR 30 BID at week 12.

The follow-up time point was 4 weeks after patients completed week 64 or 4 weeks after patients discontinued treatment before week 64.

Figure 4. Mean change from baseline in oral ulcer pain on a visual analog scale by time point through week 64 (ITT Population; DAO):

APR 30 BID = apremilast twice daily; ITT = Intent-To-Treat; DAO = Data As Observed

Note: Placebo or APR 30 mg BID indicates the treatment group in which patients were randomised. Placebo treatment group patients switched to APR 30 BID at week 12.

The follow-up time point was 4 weeks after patients completed week 64 or 4 weeks after patients discontinued treatment before week 64.

Improvements in overall Behçet's disease activity

Apremilast 30 mg twice daily, compared with placebo, resulted in significant reduction in overall disease activity, as demonstrated by the mean change from baseline at week 12 in the BSAS (p<0.0001) and the BDCAF (BDCAI, Patient's Perception of Disease Activity, and the Clinician's Overall Perception of Disease Activity; p-values≤0.0335 for all three components).

Among patients originally randomised to apremilast 30 mg twice daily who remained in the study, improvements (mean change from baseline) in both the BSAS and the BDCAF were maintained at week 64.

Improvements in quality of life

Apremilast 30 mg twice daily, compared with placebo, resulted in significantly greater improvement in Quality of Life (QoL) at week 12, as demonstrated by the BD QoL Questionnaire (p=0.0003).

Among patients originally randomised to apremilast 30 mg twice daily who remained in the study, improvement in BD QoL was maintained at week 64.

Paediatric patients

The European Medicines Agency has deferred the obligation to submit results of studies with apremilast in one or more subsets of the paediatric population with Behçet's disease and psoriatic arthritis (see section 4.2 for information on paediatric use).

Pharmacokinetic properties

Absorption

Apremilast is well absorbed with an absolute oral bioavailability of approximately 73%, with peak plasma concentrations (Cmax) occurring at a median time (tmax) of approximately 2.5 hours. Apremilast pharmacokinetics are linear, with a dose-proportional increase in systemic exposure in the dose range of 10 to 100 mg daily. Accumulation is minimal when apremilast is administered once daily and approximately 53% in healthy subjects and 68% in patients with psoriasis when administered twice daily. Co-administration with food does not alter the bioavailability therefore, apremilast can be administered with or without food.

Distribution

Human plasma protein binding of apremilast is approximately 68%. The mean apparent volume of distribution (Vd) is 87 L, indicative of extravascular distribution.

Biotransformation

Apremilast is extensively metabolised by both CYP and non-CYP mediated pathways including oxidation, hydrolysis, and conjugation, suggesting inhibition of a single clearance pathway is not likely to cause a marked drug-drug interaction. Oxidative metabolism of apremilast is primarily mediated by CYP3A4, with minor contributions from CYP1A2 and CYP2A6. Apremilast is the major circulating component following oral administration. Apremilast undergoes extensive metabolism with only 3% and 7% of the administered parent compound recovered in urine and faeces, respectively. The major circulating inactive metabolite is the glucuronide conjugate of O-demethylated apremilast (M12). Consistent with apremilast being a substrate of CYP3A4, apremilast exposure is decreased when administered concomitantly with rifampicin, a strong inducer of CYP3A4.

In vitro, apremilast is not an inhibitor or inducer of cytochrome P450 enzymes. Hence, apremilast co-administered with substrates of CYP enzymes is unlikely to affect the clearance and exposure of active substances that are metabolised by CYP enzymes.

In vitro, apremilast is a substrate, and a weak inhibitor of P-glycoprotein (IC50 >50 μM), however clinically relevant drug interactions mediated via P-gp are not expected to occur.

In vitro, apremilast has little to no inhibitory effect (IC50 >10 μM) on Organic Anion Transporter (OAT)1 and OAT3, Organic Cation Transporter (OCT)2, Organic Anion Transporting Polypeptide (OATP)1B1 and OATP1B3, or breast cancer resistance protein (BCRP) and is not a substrate for these transporters. Hence, clinically relevant drug-drug interactions are unlikely when apremilast is co-administered with drugs that are substrates or inhibitors of these transporters.

Elimination

The plasma clearance of apremilast is on average about 10 L/hr in healthy subjects, with a terminal elimination half-life of approximately 9 hours. Following oral administration of radiolabelled apremilast, about 58% and 39% of the radioactivity is recovered in urine and faeces, respectively, with about 3% and 7% of the radioactive dose recovered as apremilast in urine and faeces, respectively.

Elderly patients

Apremilast was studied in young and elderly healthy subjects. The exposure in elderly subjects (65 to 85 years of age) is about 13% higher in AUC and about 6% higher in Cmax for apremilast than that in young subjects (18 to 55 years of age). There is limited pharmacokinetic data in subjects over 75 years of age in clinical trials. No dose adjustment is necessary for elderly patients.

Paediatric patients

The pharmacokinetics of apremilast were evaluated in a clinical trial in subjects 6 to 17 years of age with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis at the recommended paediatric dose regimen (see section 5.1). Population pharmacokinetic analysis indicated that steady-state exposure (AUC and Cmax) of apremilast in paediatric patients receiving the paediatric dose regimen (20 mg or 30 mg twice daily, based on body weight) was similar to steady-state exposure in adult patients at the 30 mg twice daily dose.

Renal impairment

There is no meaningful difference in the PK of apremilast between mild or moderate renally impaired adult subjects and matched healthy subjects (N=8 each). The results support that no dose adjustment is needed in patients with mild and moderate renal impairment.

In 8 adult subjects with severe renal impairment to whom a single dose of 30 mg apremilast was administered, the AUC and Cmax of apremilast increased by approximately 89% and 42%, respectively. The dose of apremilast should be reduced to 30 mg once daily in adult patients with severe renal impairment (eGFR less than 30 mL/min/1.73 m² or CLcr <30 mL/min). In paediatric patients 6 years of age and older with severe renal impairment, the dose of apremilast should be reduced to 30 mg once daily for children who weigh at least 50 kg and to 20 mg once daily for children who weigh 20 kg to less than 50 kg (see section 4.2).

Hepatic impairment

The pharmacokinetics of apremilast and its major metabolite M12 are not affected by moderate or severe hepatic impairment. No dose adjustment is necessary for patients with hepatic impairment.

Preclinical safety data

Non-clinical data reveal no special hazard for humans based on conventional studies of safety pharmacology and repeated dose toxicity. There is no evidence of immunotoxic, dermal irritation, or phototoxic potential.

Fertility and early embryonic development

In a male mouse fertility study, apremilast at oral doses of 1, 10, 25, and 50 mg/kg/day produced no effects on male fertility; the No Observed Adverse Effect Level (NOAEL) for male fertility was greater than 50 mg/kg/day 3-fold clinical exposure.

In a combined female mouse fertility and embryo-foetal developmental toxicity study with oral doses of 10, 20, 40, and 80 mg/kg/day, a prolongation of oestrous cycles and increased time to mating were observed at 20 mg/kg/day and above; despite this, all mice mated and pregnancy rates were unaffected. The No Observed Effect Level (NOEL) for female fertility was 10 mg/kg/day (1.0-fold clinical exposure).

Embryo-foetal development

In a combined female mouse fertility and embryo-foetal developmental toxicity study with oral doses of 10, 20, 40, and 80 mg/kg/day, absolute and/or relative heart weights of maternal animals were increased at 20, 40, and 80 mg/kg/day. Increased numbers of early resorptions and reduced numbers of ossified tarsals were observed at 20, 40, and 80 mg/kg/day. Reduced foetal weights and retarded ossification of the supraoccipital bone of the skull were observed at 40 and 80 mg/kg/day. The maternal and developmental NOEL in the mouse was 10 mg/kg/day (1.3-fold clinical exposure).

In a monkey embryo-foetal developmental toxicity study, oral doses of 20, 50, 200, and 1000 mg/kg/day resulted in a dose-related increase in prenatal loss (abortions) at doses of 50 mg/kg/day and above; no test article-related effect in prenatal loss was observed at 20 mg/kg/day (1.4-fold clinical exposure).

Pre- and post-natal development

In a pre- and postnatal study, apremilast was administered orally to pregnant female mice at doses of 10, 80 and 300 mg/kg/day from Gestation Day (GD) 6 to day 20 of lactation. Reductions in maternal body weight and weight gain, and one death associated with difficulty in delivering pups were observed at 300 mg/kg/day. Physical signs of maternal toxicity associated with delivering pups were also observed in one mouse at each of 80 and 300 mg/kg/day. Increased peri- and post-natal pup deaths and reduced pup body weights during the first week of lactation were observed at ≥80 mg/kg/day (≥4.0-fold clinical exposure). There were no apremilast-related effects on duration of pregnancy, number of pregnant mice at the end of the gestation period, number of mice that delivered a litter, or any developmental effects in the pups beyond postnatal day 7. It is likely that pup developmental effects observed during the first week of the postnatal period were related to the apremilast-related pup toxicity (decreased pup weight and viability) and/or lack of maternal care (higher incidence of no milk in the stomach of pups). All developmental effects were observed during the first week of the postnatal period; no apremilast-related effects were seen during the remaining pre- and post-weaning periods, including sexual maturation, behavioural, mating, fertility and uterine parameters. The NOEL in the mouse for maternal toxicity and F1 generation was 10 mg/kg/day (1.3-fold clinical AUC).

Carcinogenicity studies

Carcinogenicity studies in mice and rats showed no evidence of carcinogenicity related to treatment with apremilast.

Genotoxicity studies

Apremilast is not genotoxic. Apremilast did not induce mutations in an Ames assay or chromosome aberrations in cultured human peripheral blood lymphocytes in the presence or absence of metabolic activation. Apremilast was not clastogenic in an in vivo mouse micronucleus assay at doses up to 2,000 mg/kg/day.

Other studies

There is no evidence of immunotoxic, dermal irritation, or phototoxic potential.

© All content on this website, including data entry, data processing, decision support tools, "RxReasoner" logo and graphics, is the intellectual property of RxReasoner and is protected by copyright laws. Unauthorized reproduction or distribution of any part of this content without explicit written permission from RxReasoner is strictly prohibited. Any third-party content used on this site is acknowledged and utilized under fair use principles.